The Jhelum flowed with nary a ripple; houseboats moored close to the banks remained unmoving. Except when passing beneath the Zero Bridge the water shimmered viridian in the mid noon sun. The rains had come and gone, thankfully without any deluge and destruction, and by April summer was peaking – the river wasn’t running very deep and one could see the green of the algae and other aquatic plants. I leaned over the ornamental balustrades of the recently restored, all-wood historical bridge, gotten used to by now to the reluctant amour of courting couples, sudden nervy movements of otherwise shiftless youngsters, a studied insouciance towards visitants, beady looks from wide boys and little scamps chaperoned by matronly ladies muttering their breath.

Built in the 1950s it was the oldest bridge in Srinagar. When the planks began to give away under the weight of vehicular traffic, it was soon decreed for pedestrians only; as insurgency peaked in the 90s, military bunkers marked both sides of its 154-metre arched span. Though no more bunkers today, there are heavily armed sentries with a cautious finger on the trigger of business-looking automatic weapons. They peered closely at my Delhi number plate as I parked my motorcycle near the ceremonial entrance lined on one side with shops with majuscule lettering all carrying ‘Zero’ in their names and on the other side with enterprising migrants selling jackets and warm undergarments from splayed open cars.

“This is the first bridge in Srinagar,” my wonderful homestay host and a teller of sanative stories had told me earlier about the origin of the name ‘Zero.’ I had no reason to disbelieve her, still I decided to ask a local, a youngster in jeans and a fitting kameez around which was fastened a frayed bumbag. He was taking selfies from the river-facing deck of a shut food court. I offered to take his photographs, which he politely declined. He was waiting for a friend.

“The bridge was built by a deaf contractor,” he said. “In Kashmir, ‘zor’ means deaf and soon ‘zor’ was changed to ‘zero’ by the Indian government.” I wanted to ask him the chances that the contractor became ‘zor’ after the bridge was built – all that hammering. But like most lads of the valley, this one too was serious beyond his years and looked distracted, fiddling with the pouch around his waist. What I dismissed as a gewgaw soon opened and a shiny chocolate packet emerged from it. The swain walked past me and nodded ‘salaam alaikum’ at a very pretty girl whose uncovered face shone like pearl from an oyster shell. I decided to stick around should they require my photography services over twofies. But soon they disappeared into the deserted lounge of another closed food court and I went back to watching the quiet flowing Jhelum with its wavy plankton life beneath and the river purlieu.

That was when I noticed the troop movement along the embankment.

Following the bomb squad

We were staying at the Dak Hermitage which was a five-minute walk from Zero Bridge; my girlfriend decided to take a siesta and I decided to step out. As I was heading towards the Dal Gate, riding over the Abdullah Bridge, the Zero Bridge that ran parallel looked out of a Montessori group activity assemblage of a wooden play city. The living boats parked next to it added to its arcadian atmosphere; a time warp from blaring city life. Dal and the now familiar sights around the more popular lake could wait, I turned around.

Somehow not much seemed out of place. Heavily armoured vehicles followed each other along a narrow lane that flanked the river, helmeted heads intent behind front sights jutted out from saucer-shaped bulletproof guichets. It was a joint operation by the counter insurgency specialists Rashtriya Rifles, the paramilitary CRPF and the Special Operations Group of the JK Police. Soon after the surprisingly quiet vehicles had passed, a lonely man garbed in camouflaged uniform billowy like an astronaut suit followed carrying a large black box. He took measured steps, plucking off each after some kind of deliberation, focused unerringly ahead. Giving him cover and following from a distance were two heavily armed personnel who kept glancing upward at terraces and open shops. I had followed the troops and now stood inside a mobile accessory shop to buy a charger, waited while a customer ahead of me chaffered coyly with the equally pleased shopkeeper lad. While the banter continued through the troop deployment, it halted abruptly with the sight of the man with the black box.

“Bomb squad,” the customer murmured from behind a veil. The man watched the street to see whether anyone was shuttering down. This was the first time in my life I was coming across a live explosive ordnance division guy – those faceless, fearless heroes tugging at fuse wires connected to their own death. Steel balled cowboys shepherding around platoons without loss of life or limb. Breathing deep, probably sweating profusely behind helmet visors, even cussing their commanders for not having adequate remote-controlled wheelbarrows. Humans behind iron facades, sometimes rendered twisted and useless. Without minding the solecism, I interrupted the resumed proceedings within the shop and asked the guy to make my bill.

Life as usual

In my excitement I forgot what sight I might have cut in my riding jacket and doffed helmet in one hand and gloves in the other but I was getting interested stares from the locals. The two armed security following the bomb guy looked at me once and I guess dismissed me like some nutty quisquous. At least on two occasions I saw guys behind doorways whipping up their cell phones from within pherans and making harried calls as we passed. Slightly unnerving, I must admit, to expect to be anticipated.

I was stopped at the periphery of the cordon and search operation – a large brick building adjoining an open area behind bolted tin sheets. There were a few lean-tos inside surrounded by well-kept, multi-storeyed buildings with small curtained windows. A soldier who could have easily passed off as a cast of the Benghazi movie cordially asked me for an ID. From Delhi, motorcycled up, flower show, travel blog, girlfriend sleeping, my answers went. From Punjab, RR, second year in Srinagar, married, father farmer, visited Singhu once, his own followed. He asked me to keep my ID in my top jacket pocket so I didn’t have to fish it out each time from my wallet – and I would be stopped more times the deeper I ventured into the coso area. He thumbed up my clearance till a couple of blockades ahead and then I had soldiers asking me to stick close to the walls after they checked my bag and ID.

Inside the cordoned off area the shops were shut and people hurried past the parked convoy. A man who had been standing watching nonchalantly with a lachrymose toddler turned around with a heavy heart and closed a fortified door behind him. As if on cue, a muffled explosion went off somewhere and from the parked trucks swarmed personnel in heavy combat gear; one guy came towards me – suddenly I was alone – and gestured at me to move back into an alley. How does one acquiesce quietly under the circumstances? Raising hands would be too much and nodding too little. Thankfully that awkward moment passed fast and I was in a deserted backstreet with tall walls rising around me.

There were more explosions – now louder and clearer – and rat-tat of machine fire. I walked fast keeping close to the walls. In my flight, I kept peeping up the walls at the windows for movement. Rains the previous evening had left puddles of muck which I jumped neatly across. Sounds of gates banging shut echoed followed by the metallic squeal of rusted padlocks. I scurried feeling like caught in a maze, heck, it was a maze: a concrete wall soared blocking my path connecting the two buildings across the lane. Most probably an illegal erection across encroached public property; I was angry, but somehow I still remained close to the contemptible wall. Left with no other option but to retrace my walk, it occurred to me that I was in Anytown Kashmir. This was everyday, life as usual.

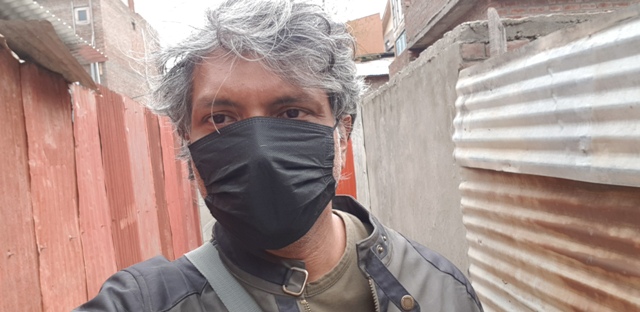

From the alleyway I sent a selfie to my girlfriend with a note.

‘Might be a little late, will wake you once am there. Love.’