There are two views from a moving car – the far and the near.

While the first is barely moving, the second is a swishing blur. Between the knolls in slow motion and the swarming swards is you. Belted into a metal capsule, hurtling forward. Over soporific savannahs, just-vanished mirages, through blinking shades of patulous ancient trees. The extremes of rushing and remaining landscapes create a time warp, a kind of nowhere where you can be anywhere. Tensions disappear on the road because of this – today ceases to matter.

We are on the Lusaka – Livingstone Road, or ‘T1’ as regulars call it. A 450 km part of the Trans African Highway network. This is monster truck territory ferrying construction and agriculture equipment, minerals, ores and automotive spares across countries and continents.

My dad used to call them Goliaths when I was little in Nigeria probably after the pet name written on one. Behind one meant a long wait, stuck, and maybe breakfast in the anvil; a picnic I and my sisters looked forward to. We would be on our way to Sokoto so my parents could do their official work or Kano, farther away, visiting other Keralan friends.

On a rare occasion when my mom took the wheel, and set about overtaking a Goliath, we kids erupted like cheerleaders during a home run. I remember the gigantic fuel tank and battery boxes at eyelevel, the axle churning in a netherworld of its own, and the tyres, furious little Ferris wheels of rubber. Mesmerizing, for any young boy, I suppose. Waking up from the reverie we had come to an abrupt halt in the middle of swirling dust, scattered lambs, and their angry minder on the wrong side of the road. Cattails swung back for a clearer look, my folks were quiet, breathing hard, and we were disappointed. I think my mom didn’t drive for a long time afterwards.

Cattails were around us now. The Zambian soil is generally fertile, dambos had come alive as the monsoon got over recently. The dambos do not look much, sometimes even have a slight putrid stench about them, but they are important, ecologically. We were surrounded by one, where there was no maize there were the cattails.

I had my window down, my friend Ace had hers up as she was on the phone, as she was mostly. The swoosh of the wind was muted, the permitted speed was 60 kmph, we were passing through Chilanga. In Zambia, like most of Africa, speed limits are taken seriously; road cameras are announced visibly and not hidden between tall boughs. Safety precautions are exercises best undertaken together and not enforced with penal fears, fomenting dissent and rebellion often with catastrophic results.

Chilanga, barely 20 km outskirts of Lusaka, was a predominantly white settlement till Zambian independence in 1964. Ace was a kid then who came with her parents to Zambia as her father had joined the newly formed Zambian Air Force. She remembered coming to the Munda Wanga Wildlife Sanctuary in Chilanga and bumping into Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte. Of course, she barely knew she was witnessing one of the greatest friendships in cinema history. Or any kind of history. The fortune in the fortuity was only to dawn later.

Ace was understandably awestruck by the two goodlooking men and best buddies. A friendship that spanned nearly eight decades and artistic collaborations; Sidney directed nine films, the first of which, ‘Buck and the Preacher’, starred Belafonte and him. But even before the movies, there was a bigger cause binding them – they were both active participants in the civil rights movement. The two were key in organizing the historic March on Washington in 1963 which culminated in the iconic ‘I have a dream’ speech by Martin Luther King Jr. Together they carried money for Freedom Summer volunteers, chased and shot at by Ku Klux Klan.

‘Buck’ was released in 1972, the same year they visited Zambia and spent time with President Kenneth Kaunda who was a good friend. It was the same year Ace met them at the wildlife sanctuary in Lusaka outskirts, a meeting she remembers vividly as a starry-eyed 15-year-old. There might have been some time spent in their presence, or with them, not sure. Despite a hugely successful corporate career and a busy family life, Ace went on to actively participate in Namibian freedom struggle.

We pass by Monze from where there is a turning towards Kafue National Park, the biggest one in Zambia. Abandoned hoks can be spotted from the road, probably a testament to its rich agrarian past. What once used to be ‘Zambia’s granary’ and a leading maize producer, has now expanded its menu to include vegetables and fruits. Some of the produces are featured in the occasional commissary but most of it is hawked by women and children on their heads, by the roadside.

They serenade motorists, singly, with their wares. They suggest purchase, but nothing approaching importunate or imploring. There is a quiet pride in their demeanour, after all, they are the Tonga people. The tribe who gave us Chief Mukulukulu, the one responsible for rain. They smiled at us, Ace by dint of her Zambia years, returned their courtesies in the local tongue. We were all happy, enjoying the hereness and nowness of it all. Monsoon was officially over about a month ago, but it rained the next day we reached Livingstone. Looked like Mr Mukulukulu was a generous chief.

There were tomatoes, spinach, cabbage, cucumber, melon, and pineapple arrayed on wood shelves bursting with viridian life and freshness. Ace tells me about the pineapples which came from Mwinilunga, close to the border with DRC, famous for their sweetness. Mwinilunga is also from where a little spring wells up which eventually becomes the mighty Zambezi River.

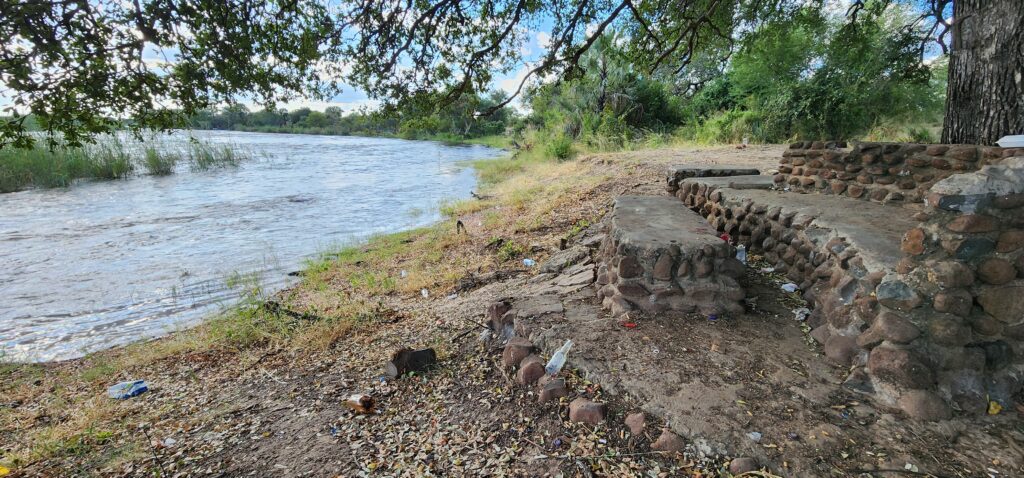

We have watched crocodiles on the Zambezi, sleepy little terrors, from the decks of sunset cruises sipping wine and nibbling on the lesser fortunate among them. We were heading to Livingstone where the Zambezi hurtles off a cliff throwing up ‘smoke’ that can be seen and heard from miles away. The name ‘Zambia’ comes from ‘Zambezi’, which flows more than 2500 kilometres through many countries before disemboguing itself into the Indian Ocean. Like any life-sustaining force anywhere in the world, here too the Zambezi has been the origin of many local lores of love. Ace had once written a poem for her college magazine, a love saga, with the Zambezi forming the backdrop. The love continues, I can see.

We stop and buy a small drum, locally known as a ‘Kaoma’. I am adding to my Africa collection. There is a lot to catch up since I left Nigeria years ago.

Since we stopped, we decided to look for a place to eat as well. We followed a signboard that read some ‘lodge’ that led us away from the main road. Lodges in Africa have a historical context – they were once the hunting lodges, near game reserves, where people stayed during season. Today they continue to mean the same, accommodations close to wildlife sanctuaries. They range from basic to luxury now.

‘Babwa Balaluma’ was written outside one house. Before I thought it was the name of the inhabitant and stopped to ask for directions, I saw the same written outside another house and ‘Beware of dogs’ beneath. So I decided not to stop and ask for directions. We didn’t find any lodge but it was a pleasant detour from the smooth monotony of the tarred road. This was the kind of road that would be marked with thin red wiggly lines on a map. Where the people you see are not busy going anywhere. You ask them for directions and they will ask you all the questions – from where did you set out, headed where, how long on the road.

My first bicycle was a Raleigh and I loved it dearly, more than any of my sisters. It had white seat and handlebars and the rest of it was red, like a Ferrari. I rode it like one – flying over hillocks, rocketing down winding paths, chased scampering cattle, geese and hornbill. One of those honeymoon days I lost my way. I tried my dad’s name and then the school on people asking them for the way back. They all gave me cheery smiles and nodding heads, some even eyed my bicycle which had me worried. I believe they must have been thinking that I came a long way on my Raleigh.

There were bicyclists on the road to Livingstone. These were small shop owners, carting clamped down large loads on their carriers. With Zimbabwe just on the other side of Livingstone this was cross border trade at work. There were people selling sacks of charcoal by the highway. Where there is coal the land is rich. Writing my book on Chhattisgarh, I found locals ferrying away large quantities of coal and selling them by the road. An illegal practice. Here I didn’t stop to enquire the legality, but apparently while a major source of income, the coal industry is also posing a threat to Zambian forests. Mining permits are more controlled today.

School children in dapper uniforms walked to and from school. I stared wondrously at their spotless shirts and skirts, with neckties to boot. My shirt used to be bescumbered after school. We passed by several little churchly shanties with fragile crosses atop. Sometimes a preacher in a loose-fitting suit could be spotted. The local poobah, the designated man of god, with his fidgety flock.

Ace once gave one of them a lift who made a pass at her. What are you doing, Ace asked. She was so hell-in with him, but more surprised at the audacity. Her kids were in the car. Knock and it shall be opened, he replied. The holy one soon found himself standing by the road, again, thumbing air. Man proposed, this time woman disposed.

Rail tracks sliced across the road at many places without gates. Even if they were used it seemed a rarity as people sat across them drinking soda and shooting breeze. The monster trucks took forever to cross one. ‘The driver of this truck has been instructed to stop at rail crossings’ was written behind some. Read like a sentence. One passed through Choma where we stopped for coffee. I stood next to it, anxiously, as a truck trundled across taking several minutes.

Choma to Livingstone was about 200 km. Fortified with coffee and munching on freshly baked corn bread, we decided to head on without any more stops. The speed limits were now lifted or were 100.

With the gloaming came the Goliaths, a searing, barrelling mangata, illuminating and commanding the right of way.

Much like the memories.