The urge to be ‘out there’, to be surrounded by vast open spaces, is as old as mankind itself. Making his argument about why it is not exactly a ‘concrete jungle’ but a ‘human zoo’, English ethologist Desmond Morris writes in ‘The Human Zoo’ that man ‘Trapped…by his own brainy brilliance, has set himself up in a huge, restless menagerie where he is in constant danger of cracking under the strain.’ Conditioned over millions of years to be on the move, to hunt and colonise new territories, we are living in conditions not natural to us as a species.

Morris tells us that our ‘brains are exploratory in nature and we struggle to cope with prolonged periods of inactivity, to be in one place for too long.’ Claustrophobia is a consequence. I suffer from bouts of it – waking up in the middle of the night I see the walls of my bedroom caving in. Only after spending some time in the park near my apartment that I am able to resume sleep. But these city parks, I agree with Morris, are a joke in terms of space. ‘The alternative for the urban space-suckers,’ says Morris ‘is to make brief sorties into the countryside.’

Sorties – or ‘runs’ in motorcycling parlance – I have been making all through my entire decade in Delhi. (Delhi and the designated National Capital Region have a combined population of over 30 million and the population density at over 29,000 per square mile is one of the highest in the world. This makes the NCR the perfect example of a human zoo.) From weekend runs to Jaipur, Agra, Rishikesh, Dharamshala and Shimla to Srinagar, Spiti, Manali and Leh further up that take longer. Probably by dint of my birth in Palai, an erstwhile farming village along the banks of the Meenachil River, and growing up in rural Nigeria – both places with abundant open spaces – claustrophobia hits me harder than anyone I know. It is so severe I can feel it in my joints. So, no knee and elbow pads for me, nor helmets that sheath my head within a snug, dark universe of its own but one that is open face according an expansive view. No offence to those kitted up looking like Shahenshah on a motorcycle but give me the sun and the wind and the edge of the skin on tarmac.

Turning down offers of accessories that came at attractive discounts – courtesy of the new motorcycle, a 650 cc Interceptor – my only indulgences were a regular riding jacket and gloves for a better grip on the throttle. The Christmas ride to my hometown Palai in Kerala from Delhi where I worked had been in the anvil for a month. I had already sold my Standard 500 cc Bullet to a collector in Hyderabad, (‘You can come and visit your bike any time you want’ – the sweetest thing anybody ever told me.) planned the route and other logistics including the first service at 500 km at Jhansi along the way.

A much-anticipated home-cooked dinner at a friend’s house in South Delhi who had just returned from a Citizenship (Amendment) Act protest organised at Jamia Milia Islamia next door; one of the first that were to erupt across the country over the following days. But this one was to go down as unprecedented in its ugliness as the cops played dirty by setting fire to public buses themselves. On that very day, December 15, 2019, the historic protests at Shaheen Bagh were also getting started; people, old women in atrate gowns, young mothers and children trickled in with little containers of food and homework books.

“It is going to be the next Satyagraha,” my friend who is also a rights lawyer cum activist had predicted.

By January 15, 2020, upon completion of a month, the Shaheen Bagh protests had gone into the annals of protest history for its sheer discipline and perseverance despite lack of any leadership. Probably because of lack of leadership the onus was on everyone. The crowd has swollen into the thousands and the authorities didn’t know whom to talk to or negotiate with. The protests were peaceful with singing, chanting, skits and reading of the Constitution. Those who were politically affiliated to the ruling BJP but flummoxed by the discriminatory law shared their dilemma publicly. The crowd responded. A makeshift library came to be set up where those looking to rest and recharge could spend a few hours. As the secular paradigms of national polity shifted severely affecting large sections of the population, protests were soon to become a way of life. And Shaheen Bagh took over Jantar Mantar as the epicentre of protests in the NCR.

Next morning before I left I told my friend that we would meet at Shaheen Bagh once I returned. In response she raised a clenched fist from the balcony and quietly mouthed,

‘Inquilab Zindabad!’

Day 1, December 16, 2019

Delhi to Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh (375 km)

Riding out I left behind a Delhi darkled by the winter clouds and the looming prospect of one the longest lasting mass protests ever in the history of independent India. Bored cops, probably dulled by overwork, redirected traffic at most junctions creating chaotic traffic snarls. Due to the onerous delay in exiting the city, I decided to take the Yamuna Expressway instead of the NH 8 which I always maintained had more character. And definitely better eateries. The glistening concrete Expressway was too clinical for my road taste but would make up for lost time.

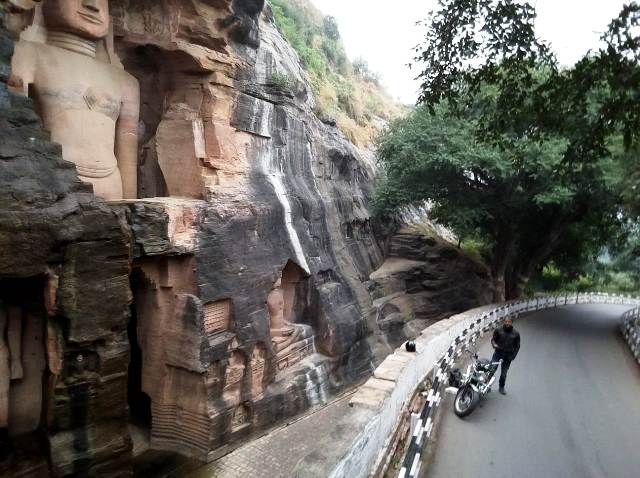

Jhansi was to be my first stop but because of the lateness I decided on Gwalior and visit the Fort with the serene Tirthankars carved into the periphery walls. The last time I came here was six years ago while working on a travel book. The saintly Jain icons who transcended samsara, or the earthly material world, sat still with their beatific smiles radiating tranquillity. Like six years ago this time too I stood across the moat basking in their Zen; a reminder set on the biological clock to slow down, take things in their stride. Let go.

The pacific quality of their faces I detected on many faces around me later. People sat around in little circles, rolled and passed joints. They wouldn’t sell their ‘maal’ simply because it wasn’t for sale but happily share a few tokes. Hashish at lower levels, opium and heroin among the affluent was a fact of life in the north. Even though the government continued to deny its widespread availability and clamp down with barbaric laws, it continued to be smuggled from across the border. I chose a property near the Fort to stay which had seen better days. Deepak showed me to my room and noting my hesitant Hindi switched promptly to fluid English. He bought out an Oyo welcome kit even though the hotel wasn’t listed under the aggregator and informed me conspiratorially that I could keep it – even after I checked out. Besides the blemishless hospitality his repertoire of services included just what a lone traveller would need – women and drugs.

“My girls are already out there,” he said waving his hand dismissively. Then he fished out a small stick of hashish from his jaded windcheater and began to scrape small granules from it. “They are very good at their jobs and are always busy.” The way he put it made him sound like Charlie talking about his angels out on a mission. Deepak was 38 years old and never married due to obvious reasons: “Why marry when what you really want is available without the heartbreak or fights?” Later, over the spliff, he confided that he was in love with one of his women but couldn’t marry her as his folks did not approve. True love is never smooth, I volunteered solemnly. Maybe, but she left him and Gwalior for Delhi.

“Somebody else is her broker now but I can give you her number.”

Day 2, December 17

Gwalior to Jhansi, Uttar Pradesh (115 km)

My first service at 500 km was scheduled at a Royal Enfield authorised workshop in Jhansi. The service advisor – the spotless guy among the lot – assured me that even though I had turned up late for the allotted morning slot he was taking me up on priority. He didn’t tell me why exactly. The mandatory checks on the air filter, clutch cables and throttle were done, the oil changed and chain cleaned and lubed. I was good till 5,000 km.

From Jhansi which is Uttar Pradesh, Orchha in Madhya Pradesh is just 20 km. This little township by the Betwa River is famous for the stately ‘chhatris’ or cenotaphs build by the Bundelkhand kings. Passing through a wildlife sanctuary where buses plied at breakneck speeds at squirming angles overloaded with pilgrims, this is also home to the famous Ram Rajya Temple which is the only temple where Lord Ram is worshipped as a warrior king. Inside he sits decked in regalia holding a sword, ready for action unlike the Ram we know who shunned violence even when his own wife was abducted.

A local heritage minder inveigled me into parting with 500 rupees for flying my drone camera. Backing his authority, he assured me, was the entire ASI machinery. Soon after the money changed hands, a sadhu, probably in cahoots with the guy, conjoined himself to me. Instead of the dreadlocks, he had hennaed erinaceous hair and an unruly beard. I still thought I did hit him up for some of the esoteric knowledge only these guys were supposed to possess. What is the purpose of life? Why are we here? I asked while taking photographs of the cenotaph from over the Betwa. He didn’t give me an answer but replied that winter was getting severe and he had to urgently buy a blanket. What about rebirths? Do we ever make it back? It’s been two days since he had a proper meal and needed to buy food, urgently. Where was he from? How long had he been in the ascetic way? It didn’t matter, he needed some money. And that too, urgently. I am sure there will be some who could glean out answers from his responses – who became the disciple-lot.

A gust of strong wind threw my drone against a clump of trees in an island across the river. I hired a boat to go across the water and look for my crash-landed drone. I asked the sadhu if he would like to come with me and help me search.

“I will be right here,” he said spreading out a newspaper on the sandstone stairway that led into the water. “And await your triumphant return.”

Somehow I knew he’d get his money.

Day 3, December 18

Orchha to Nagpur, Maharashtra (610 km)

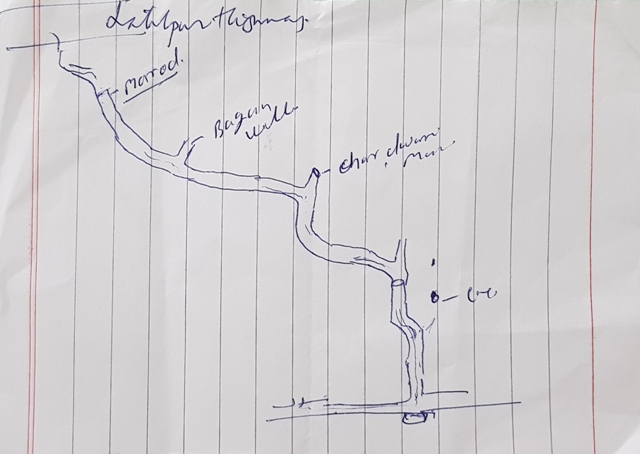

After a lit night at the Orchha Amar Mahal with some sterling Bundelkhandi performance art by the tribal folk, I had an early start for Nagpur. I rode over to the Betwa from the bypass where the hotel was located for a last look at the picturesque river. It had misted over; fog and water flowed hand-in-hand over the rocks. It wore an ethereal look like Prince Hardaul himself could be sitting on the banks before repairing to the temple dedicated to him next to the Orchha palace. Legend goes that Hardaul was the brother of Raja Jhajjar who had him poisoned for suspecting an affair with his wife, the queen. But for the wedding of some close relatives he returned from the dead. The first invites to local weddings even today goes to Hardaul at his temple. But now from behind one of the larger rocks emerged a little boy pulling up his jeans. Unthinking I handed him my mobile phone for a photo. He looked at me incredulously, wiped his hands on his clothes before taking the phone from me. After the session, I followed a short cut the hotel manager had drawn out for me on a sheet of diary and hit the NH 44.

What the manager called a shortcut was about 20 km. No complaints as it took me through some of the most bucolic scenes. The mustard fields had started blooming – the smattering of yellow flowers across a startling green sea. Thorny shrubs hemmed in the fields and kept grazing cattle away. Kids chaperoned to school by their grandfathers gawked at me with curiosity while I looked admiringly at their dapper neck-tied, freshly laundered uniforms. The houses had mostly low adobe walls with ornate wooden doors – bolted ones meant the inmates had migrated to cities seeking better prospects. Old men squatted around fires and women filled pots of water from hand pumps. As I neared the Lalitpur highway I spotted some lads revving their motorcycles and some soon were racing me.

Being the longest stretch of the ride, I tanked up twice before reaching Nagpur. There was a truck that had turned turtle along a straight stretch of the highway near Sagar – clearly the driver had fallen asleep at the wheel. But no casualties. Those who guarded the wares till back up arrived had made a tent from the tarpaulin and rested under it. As they were transporting provisions subsistence was easy. When I stopped to take a look something hot was cooking and the guys beckoned me over. At Lalitpur where I stopped for breakfast at a newly opened restaurant along the highway, Monu took my order.

Monu had one of the cheeriest dispositions I ever saw on a human and wore winkle-pickers, probably remnant of some celebration; winter was the wedding season in the north. Humming he went down into the basement kitchen, cooked the food, came back up and served me. He sang Hindi songs and mopped the floor while I ate, occasionally looking up to ask if I wanted anything more. Infectious happiness, I soon forgot my juddering knees and decided that the small motel was the least gig he could run. I told him about the various central government schemes for skilling and placement in the sector. The future-minded Monu took notes.

At Narsinghpur several signboard with ‘animal crossing’ were spotted along the road. Beneath one I took my lunch break of chocolate, nuts and water. The distant landscape faltered in the mirage under a steaming sun. I waited for nearly an hour for any sign of wildlife while drying a pair of socks on the tarmac which had gotten wet when I slipped over a rock wading into the Betwa to retrieve my fallen drone. In a parallel universe the sign would have been for them to watch out for our crossing. I sat on the roadside and wondered if zoanthropy was a willed condition which animal I would choose to become. Maybe a big cat for we have driven them to near extinction.

About 50 km from Nagpur, the perennial logjam called Pench road project starts. When I motorcycled from Delhi to Hyderabad and back some years ago, this was forestland. Langurs sat on the road tweaking edibles off each others’ hair. Once a sambar scurried across and when I stopped for some pandiculation a nilgai locked me in a stare war before springing away. I remember the stretch vividly and with great fondness. Today with the project in full swing, exempted from many mandatory environmental clearances, long distance buses and timber laden trucks heave their way in and out of half-finished stretches. Portly contractors peered intently into their mobile phones while scrawny labourers moved unhurriedly carrying tools in their hands or laden baskets on their heads. The langurs are still on the road but instead of the air of ease displayed in their habitats they looked around uncomprehendingly at the glaring, cleared areas.

Day 4, December 19

Nagpur to Hyderabad, Telangana (508 km)

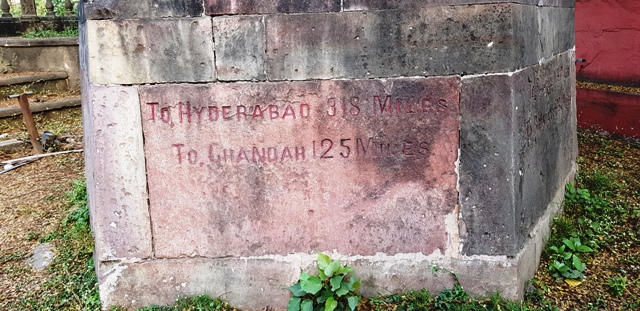

Hot water was standard feature of the property as per the website and I dreamt of pouring gallons of it over my limbs and back which had begun to ache. What they failed to mention was that the hot water came in one old paint bucket and covered with chulha soot. Then a little discomfiture is good if you want an early start. Going through some tourism literature available at the counter, I found out about the Zero Milestone. Checking out earlier than usual, I went to this British heritage passing over the Ram Jhula, a cable-stayed railway overbridge, which looked like a scaled down version of the Signature Bridge in Delhi which I had been filming for nearly five years. Apart from the practicalities involved, the fan-like design is an aesthetic marvel which never ceases to amaze me. There are bridges and there are cable-stayed bridges.

Built in 1907, the Zero Milestone was the starting point of distance measurement to different parts of India. Nobody, including traffic cops, knew it by its official name but they all called it ‘chauraha’ meaning a simple junction. Though many debate its validity, that the actual junction heading out to different parts of the country including Hyderabad where I was headed to is a testimony to its credible base. Taking cues on distance (318 miles or 511 km) and direction I started for Hyderabad from the Zero Milestone.

The highway, till I entered Kerala, is, to borrow a trucker jargon, ‘makhan-jaisa’ or ‘butter-like.’ During the trip whenever I could see an uninterrupted stretch for a few kilometres, I would open the throttle: I hit 150 kmph before Nagpur and on this stretch I upped it by another 10. Regular cruising speed was a 120 kmph, the only bummer being speed breakers that came up unannounced. While the law mandates that speed breakers should have advance warning signs, this is merrily flouted and you have them coming up willy-nilly; at high speeds these can cause the accidents which they are trying to avert. The NHAI should take cognisance of such humps and either flatten them or if they were put up with valid reasons, ensure they are announced in a timely fashion. On many occasions, I was sent cannonballing over these pesky surprises.

Day 5, December 20

Hyderabad (Pretzel and rest)

Internet connectivity was pretty robust along the way prompting me to undertake an #instatravel updated every day with related octothorpes, more commonly #dillipalai and #interceptour which I thought were respectively charming and clever. Even when I stopped by a tarn about 150 km before Hyderabad surrounded by fields and took some aerial shots with my motorcycle gleaming against the late afternoon sun – how the name ‘Silver Bullet’ came up – the mobile data was intact. So, on the rest day at my sister’s – who wasn’t coming down for Christmas this year – I decided to go device-free. Instead I spent the time catching up with her family newly extended by the addition of a Labrador, Pretzel.

Pretzel was the main reason my sister wasn’t coming home although to Mom she put the blame on her son’s 12th class board exams.

“No way I’m putting him in a kennel,” she told me. “Send my sons to a reform school maybe I will.”

Each evening when my brother-in-law returned from work, watching Pretzel going bonkers with ecstasy you’d think he was missing since the Kargil War. He would bring you the rugs and small carpets if he liked you which meant everyone who came to the house got rugs and small carpets.

“That’s the problem with labs,” the sis said. “You have to train them to bark and teach them whom to bark at.”

But some things I noticed he had picked up without arduous training – like abandoning his cot for your quilt during the wee hours. When it was time for me to leave the next day he brought a few rugs one after the other like I could have my pick – if I stayed.

Day 6, December 21

Hyderabad to Bangalore, Karnataka (598 km)

The vast open spaces of Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra were farmlands where you could see farmers toiling against all odds. In Karnataka, it was warehouses in the plains and windmills lording from over mountaintops, rotating cautiously, as if keeping an eye out for Don Quixote. Emerging from a breakfast diner I saw a small crowd had gathered around my motorcycle. ‘Silver Bullet turning heads again,’ I thought. On the first day of the trip, cruising along the Yamuna Expressway, a guy in a car had shown me the ok emoji and nodded his approval before speeding away. I nodded back nonchalantly like I was used to the adulation. But this time it wasn’t Silver Bullet.

People were walking up to a thin guy wearing shades and turned out in full riding gear and taking selfies next to his fluorescent green Royal Enfield Himalayan. ‘Ride with VJ’ was a celebrity vlogger and we got talking. Soon as I told him I was riding from Delhi he began recording on his mobile camera a new episode; he spoke nice things about the need to ride and ride long distances. The camera slowly panned out to reveal a still-preening me. I waved to his thousands of followers.

“The difficult part begins only now,” warned a cousin whom I met over coffee at Hebbal, Bangalore outskirts. He was speaking about my ride cutting across town to reach Electronic City where another sister stayed, this one who was leaving for Christmas the next day. I was a bit wabbit after the ride and the only energy left was to xertz down dinner followed by homemade cake and wine. We had to be up early the next day as half of Bangalore would be on the road to Kerala.

Day 7, December 22

Bangalore to Palai, Kerala (595 km)

Via Erode, Tamil Nadu

Even at 5 AM half of Bangalore was on the road like a re-enactment of some modern day Exodus. My back which was already messed from an old workout incident was acting up; I left my backpack with my sister who was travelling by car with her family. We passed by Hosur while it was still dark and headed into the dampness of Krishnagiri. As the day progressed the thick fog left wet dark patches on the road like rain. In a little over an hour I reached Dharmapuri toll gate 125 km from Electronic City. The toll gate was like a beehive, cars milled around like bees swarming around flowers. Pilgrims bound for Sabarimala walked by with their ‘irumudi’ as the sun slowly opened shop. They left in their wake goodwill and positivity and lot of world healing. It was a new day. My sister swung by soon and we decided on the next meeting point – a little ahead of Erode in Tamil Nadu – where we would also have breakfast.

The ‘makhan’ run ends once you enter Kerala and you are greeted by familiar sights: lungi-clad men whiling away time, cops keeping a wary eye on speed offenders, shops offering soda sarbath, whole bunches of ripe yellow bananas and state-owned transport buses who expect everybody else to make way for them. Recently the high court gave a rap on the state government knuckles over the poor condition of the roads but with clearly no effect. Despite proper craters, there is no dearth of speed cameras; in one stretch before Trichur I counted over a dozen in as many kilometres. It was like blackmailing somebody – after you mugged them.

But I didn’t care, I was riding. And I was ‘out there.’ Despite the stifling humidity – I had doffed my jacket too and left it in the car – and the jarring condition of the highway which had become NH 47 from Salem in Tamil Nadu onwards – a collusion between potholes and speed-breakers – I went full throttle. There was no way I could improve on the 160 kmph which I hit approaching Hyderabad because of the traffic and road conditions. But it didn’t matter. The sun was on my face, the wind whooshed over the rest of me. I passed by sparkling verdure, somnolent rivers, gushing dykes framing paddy fields and swaying palm fronds.

A sortie into the countryside.

(My Mom had kept the clipping for me from the vernacular paper about how a Danish word meaning ‘contentment’ had made it into the English lexicon. The word was ‘hygge’ and I loved it soon as I heard it. This post is dedicated to her not just for the fabulous word but also for being the last one to know about #dillipalai. My sisters and I decided to keep it from her knowing well her BP would run haywire.)

That bike of yours is a mechanical beauty! And the views are mesmerising especially the ‘cenotaphs of Orchha’ is really wonderful architecture. Good article. Keep it up, cheers! 🙂

Your bike is a special bike for you. It is best suited for travelling. I like your articles. Have a safe ride. 🙂