Disclaimer: You are forgiven if you start to strut about, one hand behind your back, head tilted at an imperious angle. No hard feelings if you give the gardens a critical once over, though impeccably maintained your disdain frowns forth. However that glint of pride in your eyes is hard to conceal – can be espied even from the resplendent ramparts above. After all, one fifth of the world is under your dominion. You might stop short of addressing your friend ‘my lady’ but there’s a mammoth five-glass landau clip-clopping up the cobbled stone pathway, dainty lace curtains drawn across the windows and the thoroughbreds’ mane brushed to a glisten, must be the vicereine.

The pahadis or the hill folk are infinitely hospitable, always were.

‘No tree was to be cut or cattle slaughtered’ was the sole mandate from the local chief to Captain Pratt Kennedy, political agent of the Queen to the hill states, who set himself up in Shimla in 1822. It was just the previous year that Major William Lloyd saw the Jakhu Hill – on which Shimla was originally located – for the first time and gasped. ‘I felt as if I could have bounded headlong into the deepest glens or spring nimbly up their abrupt sides with a daring ease,’ he gushed in his journal. ‘I shall never forget this day.’ Taking cue, over the next few decades thousands of English nobles who went under the suppressive mainland weather shifted homes and by 1864 it was officially anointed the summer capital of the English Empire. What came of the chief’s directive is anybody’s guess. Whole hillsides of resplendent pine forests made way for the growing town. Today from a distance Shimla glows back at you like an expansive reflector used for film shoots. Yet to hear of global warming, the weather continued to be cuddlesome; think honeymoon and we’d say ‘Shimla.’ At least our folks did.

Shimla thus grew. And how. For every cedar felled, a lodge came up. Shady touts swarm you offering rooms for rent by the hour. If you were alone they’d throw in chudi-clad call girls too who really work at passing off as the new wife. Traffic snarls snake for winding miles. Snowy winters are soon slated to be stuff of distant memories. The national green tribunal is fighting a lonely battle against the state government to introduce CNG vehicles in the hill station to reduce pollution; its queries on illegal encroachments into public and pedestrian spaces remain unanswered. Rundown buildings are whitewashed, stacked with wrought iron furniture, slapped on fancy signboards and passed off for heritage properties. Shimla today is just another overcrowded hill station – like Munnar or Manali, Kodaikanal or Khandala. The Shimla which Major William saw or Captain Kennedy set hearth is no more; would have definitely broken the heart of the chief who decreed no trees be cut. Then not all is lost in this paradise.

As you head towards Shimla along the National Highway 22, you reach the Tuti Kandi bypass; here you can either continue towards Kufri and other places beyond Shimla but opt for the depressingly clogged route up to the city. A hundred or so metres ahead, there is another bifurcation; one leads to the heart of the city and another up the Observatory Hill. Park your vehicle at the gate and saunter up the rest of the way. Though you can take a cab up, I recommend you take this walk along pine trees and mulberry plants, the cacophony of the town would have receded into a faraway hum. When you reach the top of the hill, you are still panting but your gasp is audible. It is resplendence in grey stone. The course of the subcontinent’s history was charted in its hallowed premises. Built for a whopping Rs 38 lakh during the 1880s, the Empire held sway over the world from here. Even more than a century later, the magnificence of the Viceregal Lodge continues to enthral, its eclectic intricacy captivate and thankfully, the views are still spellbinding. (One of the most memorable sunsets of your life guaranteed from here.)

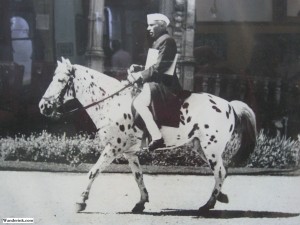

A mix of English Renaissance, Tudor and Gothic styles, the Viceregal Lodge was the official summer residence of the governors general and viceroys posted in India. Designed by Henry Irvine, the lodge-warming was during the tenure of Lord Dufferin (1884 – 88). The Lord and his lady are believed to have contributed a great deal to the designing and detailing of the interiors. The grand entrance to this baronial edifice leads to the reception hall and faces the grand fireplace. The hall is done up with elegant chandeliers, high ceiling and panelling of Burmese teak. A stairway of fairytale dimensions winds up all the way to the third floor covered in plush red carpet. Light from the sky windows above peter down, reflecting a golden orange on the ornately carved gigantic teak pillars. The rooms of the Lodge are designed around a gallery adorned with historical photographs. My favourite was that of Jawaharlal Nehru arriving for the Shimla Conference of 1945 on a polka dotted horse, files under his arms. Inject elegance and intellect to the Annie Leibowitz shot of Arnie on the horse and this would be what you get. Did it speak volumes about the man and the irresistible charm he held for women!

Breaking your reverie is the voice of the guide – there are conducted tours at regular intervals – who points out a small writing table on which apparently the fate of the subcontinent was sealed following the breakdown of the Shimla Conference.

“See the crack that runs all the way across the table?” He asks. The crack is more a wedge and hard to miss. “Some say the table cracked as the document to divide India was signed on it.” I peer close like everybody else. Though we are a country of magic and myths and mystics, this one was sort of hard. “But that’s just a wrong belief.” He said and there was a collective sigh of relief. The pleased-as-punch guide went on to say how half a dozen other tables at the Lodge had the same wedge across it. Probably it was never meant to be a writing table in the first place. The tour is over fast for the Lodge now houses the Indian Institute of Advanced Study – a higher place of research for scholars. A master move by President S Radhakrishnan which ensures the property is preserved that too by the central government. The ballroom is converted to a library and visitors are not permitted. Your access – as a tourist – is limited to the gallery and the ante rooms.

Once outside it’s not hard to see why the British chose Shimla as their home away from home – its late afternoon and the drizzle has made way for a swamping mist. You cannot see what’s around the corner or on the other side of the garden. The grey stones of the Viceregal glisten eerily with the promise of a scandal. A short walk from the Viceregal is a dilapidated, empty church distinctly from the same era. The caretaker stays in a new building constructed in the same premises. The reason for the criminal oversight is very simple: The Observatory Hill with the Viceregal Lodge comes under the purview of the government of India while the land on which the church is situated is state-owned. With a laden heart I head back to the Observatory Hill grounds.

Early darkness looms over the mesa silhouetting the Viceregal. The cobbled pathways take me to a stone bench. The Viceregal continues to cast its spell over me. It epitomises everything for which we take a shine for the British – powerful, stately and grandiose. It holds fort but misses the boat – statistically less than 10 per cent of tourists to Shimla come here. For the life of me I don’t understand why we don’t – or don’t want to – see the Viceregal Lodge.

Poor blighter! I will ponder it over high tea from the cafeteria next door.

Imperial ingenuity: The Viceregal Lodge was a hallowed party ground; maharajahs and chieftains, nobles and influential businessmen vied with each other for an invite from the viceroy to dinner. With so much power converging at one place – and so much wood work around – safety was a prime concern.

The Viceregal Lodge which was also the first building in Shimla to have electricity supply had a simple but effective fire fighting system in place. Water pipelines crisscrossed the man-high attic area with intermittent sprinkler valves kept shut by wax. In case of fire, the heat would melt the wax, opening the valves, causing water to gush out. In addition to these, the cafeteria where I retired to mull things over was earlier a fire station – right next to the Lodge itself.

(All the titled photographs – except that of Nehru – in this post including the two above are courtesy of Cutting Loose.)