Night descended on the Tirthan Valley without much ado. The shrilly, tremolo notes of swamp toads and crickets did not besiege us from all around but piped up sporadically, almost like an afterthought. Tiny rounded silhouettes rustled between the deodars by the side of the narrow road. The moon waning into Ramadan-crescent shone brightly above the overarching forest canopy. Beneath it was pitch dark and we had to use the flash lights from our mobile phones. Mountain peaks traced billowy outlines against the pearly grey sky before lumping downward and walling the river from either side. The river itself spangled silver, snaking around the chalky white of the boulders. The chirping and cheeping of wild avifauna could be heard from afar. Electric bulbs glowed like lanterns in the houses that deliquesced into the cliff side of the distant rising horizon. Around us was a yawning valley snuggling into the blanketing night.

The joy was infectious and the walk worked wonders for our appetite. We were invited for a dinner of scrumptious trout, salad and fruits by a friendly resort owner and soon enough we were all drunk. So drunk that our host revealed his secret stack of yarsagumba, a prohibitively expensive and potent aphrodisiac found in the high altitudes and offered to make us all soup from it. And I almost took up somebody’s offer to teach me shirshasana when somebody else pointed out that the two-litre whiskey canister was nearly empty. Even without standing on my head the world had gone ahead and done a turtle on me. And a hazy, whirly one at that.

On our way back from dinner, which redefined the world order, a sprightly shower fell for a short while which left the trimmed swards around the resort glittering. Each blade of grass reflected the moon, a shimmery shard. Or maybe it was my out-of-focus vision. A dog slithered away into its own shadows to resurface somewhere else as part of a barking choir. Some locals walked by wafting over us tangerine breaths, by-product of ‘Kullu No. 1,’ popular local liquor. Our slurry attempts at friendship were met with deference going back to ostlers of yore. Maybe it was their way of showing respect to tourists from big cities. Or maybe they were thoughtfully giving a wide berth in case we fell headlong. Vehicles that brought in trekkers and cyclists from the cities were parked on either side of the road looking as incongruous in the shady glades as a chaise in Gurgaon.

After a symbolic hailstorm early next morning, the valley stood robed in sparkling sunshine. A cool wind laden with fragrance of the rainwashed forest and fresh earth crept broadly down the mountaintops through the French windows and into my room in Dehuri. I lay in bed, unmoving, staring out through the window marvelling at the beauty that surrounded me. Did we as a race of miners and lumberjacks and dam builders deserve to be pampered by so much natural beauty? Is nature really so forgiving – giving us so many second chances? Or just keeping a straight face till apocalypse? A lone eagle flew far above the promontory that overlooked my room, circling around its eyrie hanging from a leafless bough of a half-burnt oak. It seemed to be eyeing me from so high above. Were our designs outed? When I was almost sure that our eyes locked a knock at the door announced breakfast.

I fled from the room.

Hellish ride, heavenly tide

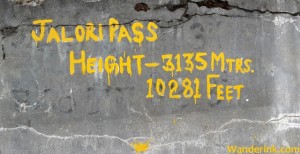

There is only so much – and so many – a sedan can take. True. And to make matters worse, one of the passengers had crested the Jalori Pass a few months ago when it was iced over in an SUV pumped up with plenty of adrenaline and prepped with silicone that it looked – and performed – like a freak hybrid between a Mars Rover and a Hummer.

“Are you sure you can take the car over the Pass?” I was asked many times.

“Remember it’s only a sedan.” I was told too, many times.

Till Dehuri I just had to make sure I followed the basic etiquettes of mountain driving and crept along close to the hillside and dove into shoulders when the more experienced Himachali drivers tore down upon me at breakneck speeds. But now looking at the photographs of the exploits of the Hummer-Rover up in the Pass it looked like I also had to sluice across slush a few feet deep, pound through waist-high snow or swish by with half the tyre jutting over the ledge making way for the bus. Why not drive through a few snowmen too? Just the kind of stuff cut out for a city-slicker sedan with a Delhi driver (for whom ‘off roading’ means ‘stopping on pedestrian crossings and cutting over footpaths’). But must say for the sedan, save for a few underside-whuppings it managed without event. Thanks also in part to an early start which saw to it that the usually crammed Banjar market (15 km from Dehuri) through which the main road cuts across at an unholy angle was nearly deserted. At eight o’ clock in the morning it lay there, a shiny, slippery vein, vehicles parked on either side with just enough space for me to slide through. I felt like doing a Pope – gleefully smackering an alien land.

Happiness and good humour had settled in from Dehuri itself – a tiny hamlet serenaded by brooks and streams, with a stout deodar doubling up as the transformer, where every man and his dog is friendly and the one liquor shop around for miles. Not much was spoken among the travellers save for smiles and nods pointing out the scenery – which was getting incredible with every turn. The sun contended itself to lacing the clouds with a jagged sheen. Tall, ancient trees stood unmoving against a powerful gale with just the leaves rustling – probably how they laughed when tickled. As we continued to ascend, the wind got only stronger – and louder, the only sound that broke the silence of the sylvan surroundings. We reached a freshly showered Banjar which meant wet roads and overflowing drainages. Homestays and restaurants occur with an increasing frequency from Banjar to Jibhi and onward, all the way to Jalori, another 10 km away. In between as you pass through Bagi, Ghayagi and Shoja you spot some droll ones too – discreet behind wild creepers and watching over organic farms. The amenities are basic but the views are priceless.

Trekkers note: Chehni Kothi, a 1500 year old castle, which belonged to Rana Dhadia, once-ruler of Kullu, is a short detour between Banjar and Jibhi. Sort of conical in shape, this castle is made along traditional lines of architecture using wood and stone. The devastating earthquake of 1905 reduced the original 15 storeys to 10 today. The ancient pagoda-styled Rishi Temple at Bagi is another popular sight around Banjar; the deity here is believed to possess powers that grant sons. The Sirolsar Lake is a moderate, hour-long trek from Jalori, doable even if you are only passing through.

Whatever that ran for a road dissolves into an impossibly craggy gradient from Shoja, five kilometres from Jalori Pass. But before you peer over that precipice, park your vehicle by a shoulder – it would be a while before you resumed your journey. Clouds hemmed in the valley from all around. The frothy sea had lapped up the landscape. Hilltops rose like little Atlantises, mysterious, shrouded by the cotton sea. Taller trees stood stoic like the mastheads of doomed ships. What added to the sublime quality of the scenery we beheld was the utter stillness of the clouds and their opacity. They looked as if they had been dropped into their respective places by a divine hand. The universal jigsaw puzzle, solved. Stunning beauty of any variety has that strange emasculating power usually ascribed to the knee area. But for us it was the powerlessness to move. We just stood there transfixed till a French guy wearing WW II goggles, riding a fancy bike with a sidecar juddered by. ‘Ten years on the road’ or something to that effect was written across the hood frame.

His passage elicited different yearnings in each of us. We watched him disappear around the next corner and reappear from the one farther below. By the time we turned back a mild breeze had massed the chops into a swirling swell.

You just love writing, as much as you love travelling. I can see that. You love word painting and working up images that think and feel. I admire that. Your opening paragraphs are always conjurers.

Now tell me about the hyperlinks, why are they linked to other pages? References to previous writing?

‘Word painting’…I like that! Oh, the hyperlinks are just an intelligently innocuous way of telling the reader ‘hey I’ve written about that too…’ And thank you for the kind words, Kchi. Coming from the one doctorate in the family. Muah!