Shangri La is fiction.

We know it yet we look for it everywhere. First described by English author James Hilton in his Lost Horizon, it has Tibetan roots – from Shambala, a mythical kingdom as per Buddhist beliefs. Several ancient adventurers from the East and the West, modern day explorers and television presenters have set out to find it. Some zeroed in on the Hunza Valley along northern Pakistan’s border with China, an isolated verdant region along the western side of the Himalayas – which Hilton also happened to visit a few years before bringing out the book in 1933. But missing here was the all-important Buddhist connection.

James Hilton, in a later interview, attributed a lot of his research to the travelogues of French priests Regis and Gabet who did a roundtrip from Beijing to Lhasa along the Chinese province of Yunnan in 1844. Along with Yunnan, Sichuan and (understandably) Tibet too have laid their stakes to Shangri La. Celebrated television presenter and historian Michael Wood suggested it to be somewhere along upper Satluj Valley. American explorer Ted Vaill whose Finding Shangri La premiered in the 2007 Cannes placed the fabled kingdom along the Muli area of southern Sichuan province. Not Muli and not fiction but a real place, said Martin Yan in one of his Hidden China episodes, Life in Shangri La. Yan said Shangri La was a living town in northwest Yunnan and filmed himself with the farmers, shopped at the crafts shops and sampled local fare. As the tussle for the title goes on, Yan’s discovery is seen by many as a desperate nip at the baffling shroud of secrecy Shangri La continues to be cloaked in.

The quest continued without respite. For a while Shangri La slipped back to what we always knew of it – an unreachable, barely fathomable concept. A paradise we will never enter, a goal we will never reach, an acme we will never crest. It became synonymous with El Dorado or Fountain of Youth or the Garden of Eden. Aiding this was Hilton’s own geographical description: an earthly paradise, a mystical harmonious valley, isolated from the rest of the world. What further piqued our interest even egged us on were probably the people traits of this Himalayan utopia: Living beyond normal lifespan, aging very slowly and permanently happy. Permanently happy? Okay, at least happier than the rest of us. The GNH – gross national happiness – to prove it was a bonus. Which brought us to Tibet’s – as well as that of all the other claimants’ – next door neighbour Bhutan.

Sitting in splendid isolation along the eastern end of the Himalayas is this little misty and mysterious country which opened up to the rest of the world – and tourism – only during the 70s. It was shortly followed by the then-King’s proclamation that he cared about GNH over GNP, gross national product, the more conventional method of measuring development. More than a radical notion, it was the monarch reaffirming his commitment to ensure the preservation of Bhutan’s millennia-old traditions and culture, conservation of environment and securing a good quality of life for the people. Must say the efforts did pay off and a few years ago Business Week magazine voted Bhutan as the happiest country in the whole of Asia. A baffling but happy contradiction considering Bhutan, with a total population of less than a million and a per head income of around a hundred dollars a month, is one of the least developed and poorest nations in the world. Then, what does money matter when we are talking happiness?

The world is flocking towards Bhutan today probably hoping some of this happiness to rub off on them. ‘As the dollar gets on the escalator and the rupee on the ventilator’ holidays have become shorter and the travellers picky. Travel agents are barbecued on iron palisades and expected to conjure up itineraries that deliver the best of both worlds – great sights and experience. Thanks to Bhutan, they are throwing in lessons in happiness as well. The basics of GNH – more a spiritual than an economic metric of development, it is development minus the destruction. That the country still has over 70 per cent of forest cover is probably due to the GNH; making it a virtual paradise for trekkers.

Bhutan is still mostly forests and paddy fields nestling at the bottom of the Himalayas; agriculture is still the only industry with over 60 per cent of the population engaged in it. Mountains crisscross the length and breadth of the land with intermittent rivers gushing by – giving rise to some of the most spectacular and bio diverse valleys in the continent. In order to preserve culture, it is mandatory that everybody wear the traditional gho and kira (for men and women respectively) to work and during national celebrations. The architecture – right from the Paro Airport to that of individual residences – is uniform along traditional Dzong lines with triple-arched windows and religious icons. Folklores are part of everyday life; flying animals and reincarnated monks weave their way into casual conversations. Gender equality is the order of the day; in fact the women are more than equal. The fairer gender run households and whatever is accumulated by a husband and wife together ultimately belongs to the wife. Another quirky fact of Bhutanese life is that one of the spouses in a marriage is allowed to have multiple partners legally – but not both at the same time!

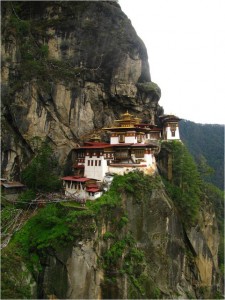

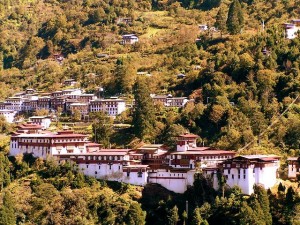

In the words of Hilton, as in Shangri La, in Bhutan too everyone is ‘guided from a lamasery’ – and there are 40 of them, each of breathtaking beauty. Popular Bhutan itineraries like the Chung Druk, Bumpa, Meto and Dhug tours by online travel agency Yatra includes visits to quite a few of them starting with the Rinpung Dzong at Paro which is also the country’s only international airport. The Taktsang Dzong monastery perched kind of perilously on an escarpment is simply jaw-dropping. Other must-sees include the biggest of them all, the Tongsa and the Punakha Dzong by a gurgling rivulet. Not just in the monasteries but the compassion is omnipresent and overwhelming; even in the mellifluous motions of the traffic cop at junctions (there are no traffic signals in Bhutan). Fishing and hunting are banned in accordance with Buddhist diktats. Internet reached the country only in 1998; refrigeration is still dismissed as an unnecessary luxury. Plastic bags are prohibited and tobacco is virtually illegal. All adding up to health, longevity and happiness.

Then, as with every happy tale, not everything is honky dory here too. The newly anointed Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay called GNH ‘complicated stuff’ that ‘masked issues like chronic unemployment, poverty and corruption.’ Despite being lauded by economists like Jeffrey Sachs in the past, GNH has in recent times come in the line of fire from critics who dubbed it ‘government needs help.’ There are problems cropping up typical of any developing nation like land encroachment, population explosion, rising technical divide, even crime.

Bhutan was a sleeping beauty who woke up to find an entire world in love with her. Tourism is indeed the biggest revenue earner and it thrives on the free flowing happiness.

Shangri La is no more fiction.

5 Comments

Arvind Passey

Large chunks of sheer text… difficult to read, but certainly quite informative.

All the best!

Arvind Passey

http://www.passey.info

wanderadmin

Thanks Passey…right about the ‘chunks of text’. Then, I write for the serious travel reader – looking for real time, pertinent information. And maybe I try to sway the reader to go as well… The other option is to put up pix and pass it off for a thousand words.. I will do that too, soon 😉

Meena

Very nice bit of travel writing on Bhutan. Next time, would be nice if you included some nice info on the birds, orchids and the bounty of nature in Bhutan.

Meena

wanderadmin

Will surely do that next time around… here I tried to make ‘happiness’ the focus of Bhutan travel.

Thommen Jose

Will surely do that next time around… here I tried to make ‘happiness’ the focus of Bhutan travel.