‘Tatti par mitti.’ Soil over scat.

So suggested the Mahatma when he realised the enormity of the sanitation mission he had undertaken along with the relentless fight to uplift the untouchable bhangi, the scavenger. Bindeshwar Pathak, Gandhi’s successor in this seminal work, incidentally also referred to as ‘bapu’ by many, started the Sulabh Sanitation Movement in 1970. His much-lauded two-pit system was a low cost toilet technology that was indigenous as well as sustainable; it was eventually replicated and scaled up as thousands of Sulabh Shauchalayas (toilets) across India and the world. In fact this ‘toilet technology’ was an extension of his crusading work among the scavengers – who earned their living by manually collecting and disposing off the ‘night soil’ – with whom he lived during his days with the Bhangi Mukti (scavenger liberation) cell of Bihar in 1968. Sulabh continues to repatriate through livelihood skill training these ex-bhangis and their family members so they can get profitably employed in more agreeable occupations.

For the hard-fought dignity to make meaningful inroads the act itself had to be cast in respectability. Many reasons have been attributed to why relieving always languished as a lowly act: the organs of defecation being sometimes the same as or very near to sex organs those who wrote about it were regarded as ribald and risqué – unworthy of literary acclaim. Among the very few French and English poets who dared to defy convention – and repudiate rewards – like Claude le Petit and Gilles Corrozal was an Indian shayar, poet, from Lucknow, Chirkeen.

Chirkeen se munh chhipaoge, bait ul khula mein kya

Be-pardah ho gayi kahaan, phir raha lihaaz

(‘Why do you hide your face from Chirkeen when you are doing toilet?

Having seen you in that state, why so modest now?’ The poem is a taunt to a lover.)

Then Chirkeen had his own reasons: While one contention is that he began waxing lyrical about defecation after his early works, ‘regular’ ghazal compositions, were stolen. The second, more plausible one is attributed to an intense dislike for the obnoxious high-brows.

On Pathak’s part, he set up the International Toilet Museum.

The museum traces the evolution of toilets over millennia: Pinch your nose but the earliest sitting/indoor toilets were not in any western country but in India! Excavations at the remains of Harappan civilisation in Dholavira, Kutch of Gujarat, reveal underground drains, water reservoirs and bathrooms – dating back to 2500 BC! Among the many interesting exhibits are the toilet etiquettes as laid down in ancient Indian manuscripts like the Manusmriti – different for the single, the married and the celibate. My favourite was the throne of King Louis XIV of France which also doubled up as a privy – apparently he used to give audience while reliving himself. Though we have no idea how this might have gone down with the courtiers and the public, dignifying the dump has continued to this day in many avatars: Virgin owner Richard Branson has his toilet placed at the topmost point of his Necker Island and he calls it his ‘throne’.

A collection of trivia shows an elephant in a Thai zoo being given potty training to save the tourists from the ungainly sight of the dungs. (How better would be the sight of a jumbo folding itself over a behind-ware that resembles a tiered mausoleum I’m not sure.) One is also ‘informed’ maybe a tad cattily that Ben Affleck bought Jennifer Lopez, whom he was dating then, a jewel-encrusted toilet seat. Then there is the costliest toilet – a hi-tech one developed by NASA; yes, for the $19 million, it converts pee into potable water. In a Time magazine compilation, the Sulabh International Toilet Museum ranked the third weirdest in the world after the Phallological Museum in Iceland and the Bard Art Museum in the US.

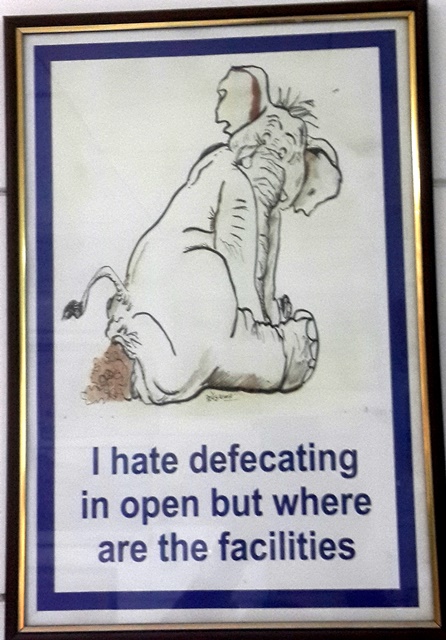

What Sulabh sought to achieve – removing the stink and stigma surrounding the scatological – was driven home by Stand Up Planet, a comedy act seeking to address global issues by making light of it, typically by raking up the stink and the stigma. From calling the ‘gleaming bums’ lining rail tracks ‘full moons’ to why open defecation is a great form of national defence, and my pet perv fav which shows two ‘shit shovellers’ appointed by the Indian Railways beginning their own day shitting on the tracks, the comedians of SUP have been at it for a while now. In addition to the LOL-performances, there are poignant infographics and interviews outlining grim statistics: one in four girls drop out of school every year as there are no toilets. In a country where 70 per cent has no proper sanitation facilities, 30 per cent of women defecating in the open are vulnerable to sexual assaults. The recent rape and murder of two teenage girls in Uttar Pradesh was allegedly a noxious mix of sexual predation and caste politics: the dalit girls had gone out at night, escorting each other, to the nearby fields as their houses had no toilets.

“Constructing more toilets is extremely important,” said Prime Minister Narendra Modi during the launch of the Swachh Bharat (Clean India) Mission on October 2nd this year. “I feel pained to see mothers and daughters go out in the open to relieve themselves.” Wielding the broom at a slum cluster in New Delhi, it was an earnest if symbolic start to the clean-up drive which will cover more than 4,000 towns and cities over five years. For ambitious programmes of this magnitude to be thorough and comprehensive, inclusive and long-lasting there has to be more than new toilets: A new mindset.

Na main gandagi karoonga, na main gandagi karne doonga.

“I’ll not litter nor will I allow anyone to litter.”

The pledge Modi made everyone take on the occasion is a good start. But as mindsets are moulded young this event too – or especially this one – should have found its way to the classrooms like the Teachers Day address.

We all have to do the same thing: dig a hole in the ground, which is soft and sandy, luckily. Put the excavated earth to one side. The crouched position facilitates and favours the age-old act. It’s best not to spend any longer than necessary, for the momentary smell immediately attracts a cloud of various jungle insects. You clean yourself with paper, if available. Then you fill the hole and replace the earth, making sure everything’s well covered. With the shovel over your shoulder and face more relaxed, you stroll back into the settlement. Hector Abad, ‘A Rationalist in the Jungle’

Museum timings: 10 AM to 5 PM, everyday except national holidays Location: Mahavir Enclave, Near Dwarka, New Delhi (around 6 km from the Delhi airport)