Mangal and the state of happiness

Two seemingly disconnected sights abound in parts of Himachal Pradesh – cannabis plants growing in disarray by the roadside and cafes announcing Israeli culinary delights. Then, there has to be a connection. Going by history at least.

History: Charas – made from the resin of the cannabis plant – has been billowing heady out of sinuous chillums in the country for thousands of years as part of religious rituals and culture. Though there was a clampdown on the drug and its users during the 1980s, it still continued to be consumed with abandon by the sadhus of the Naga tribe and other tantric sects. Mostly by the followers of Shaivism which is the sect of Hinduism venerating Lord Shiva as supreme. Though charas is grown in plentiful in countries like Nepal and Pakistan and finds its way to India through porous borders, the best quality is home-grown – grown in the Parvati Valley and Malana regions of Himachal Pradesh.

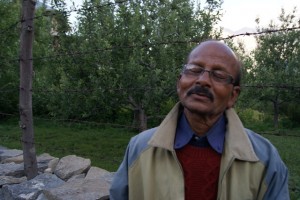

“The Israeli boys come here mostly for the good quality charas,” Mangal Singh Negi told me sitting behind the counter of his cafe-cum-provision shop. “As you can see it’s so freely available you can literally pluck it off the roadside.” Seeing me look around for a possible windfall he added, “Though we leave those for the less fortunate sadhus or beggars.” I looked back at the frothy sweet coffee I was drinking, sitting under the awning that slanted over the empty pavement on a clear sunny afternoon. I looked over at the huge Ganesha painting that hung behind the counter.“This is my art,” Mangal announced proudly. “I am artist too.”

When I announced my intention to take his photograph, he shouted something into a backdoor and out came Wangzin, his Buddhist wife, holding a pair of dark glasses. Donning it, he posed as the wife beamed. She said something which earned her a gratified smile from Mangal.

“See my beautiful wife,” he said looking at his beautiful wife, “I met her when I was posted near the Tibet border. You see, I was in the army.”

The beautiful wife smiled more beautifully and said something else.

“She is saying,” Mangal ventured a translation, “that she could not say no as I was very handsome.”

“And talented,” I added to which the beautiful wife agreed wholeheartedly.

“Hardworking is better than talented,” Mangal corrected.

I tried to peer at his eyes through the tinted glasses for any hint of sagacity. But they sounded more like words of experience than wisdom.

Shikla, ratwoman

John Steinbeck took his dog Charley with him on his road trip across America in ‘Travels with Charley’. His wife agreed to part with the ageing loyal to look after the author in case he ‘got into any trouble.’ Of course, Steinbeck did not subscribe to this but took Charley with him nevertheless. Thus was born the delightful classic lavishly strewn with attention to specifics, characters that are seamless extensions of the weather and harvest cycles of the states he passed through, a narrative bordering on fiction, an evergreen travelogue.

Now, Shikla Katoch with her pet rat Pinky may not spawn a tale of that league or magnitude, but her travels do reflect some of the original’s amusing anecdotes and whimsical vignettes. I met Shikla during a trip to Himachal Pradesh. I was waiting at the main bus depot in Shimla for a bus that would take me to Chandigarh and to Delhi. Shikla too was on her way to Delhi but her trip would continue all the way to Agra and Jaipur. A student of bio technology at a college in Solan, Himachal Pradesh, Shikla was a passionate traveller and by her own admission took off during ‘any weekend which had more than a Saturday and Sunday.’A discarded purse was rigged with holes, lined with tissue paper and was hung next to her backpack which was Pinky’s travel case cum house.

“Sometimes she hangs about my shoulders, taking in the sun and watching people.” Shikla said.

“Doesn’t she run away?” I asked. The closest I ever came to rats was reading about them being employed by pharmacy companies. Those guys, I believe, would scoot the first instance.

“Oh she won’t,” Shikla replied, nuzzling her nose against Pinky’s. “She knows how much I love her.” Then, after easing Pinky on to her shoulders, Shikla hushed conspiratorially.

“You know, Pinky thinks she is too good to be digging in garbage cans like them other rats. And I also believe that she enjoys the look of surprise in others’ eyes when they see her gambolling all over me.”

“While most jump back at the sight of a rat, even scream,” Shikla continued, “some still come forward and talk and I make many friends.” Even at that odd morning hour, there were several others who were waiting to talk to Shikla and take photographs of her pet. For a brief while, Pinky returned the bewilderment and then scurried off to the papery confines of her hanging camper.

Dey, an unending odyssey

“But 12 years was such a long time to wait for anyone,” I opined. “How much ever you love them.”

“Maybe,” Dey replied. “But you won’t believe the places I have been to and stayed because I have been travelling. All because she dumped me.”

“Probably she had to wait a tad too long before I was free of my responsibilities as an elder brother,” Dey justifies the spurning of his love. “Anyway, after it happened, I took voluntary retirement.” And thus began an odyssey that continues to this day. He has been all over the country, staying mostly in ashrams and sometimes even working for his next passage.

“Once somebody got to know about my experience with a big company, I get job offers as a hotel manager or accountant.” Dey never could remain in a place for more than a few months; soon the desperation would raise its ugly head and he would feel the restlessness settle in almost like a desired antidote. And Dey would be off. He needed to be by himself, on the road, to feel alive. He learnt the hard way never to take anything for granted, especially something as fickle as love.

Dey had been the manager of the little hotel on a hillside in a small Himachali hamlet where I was staying. He had been there the longest – close to a year – because the owner had become a good friend.

“I will still be leaving soon,” he said. “I lied to him that I am getting married.”

It seemed like he wanted to, in the words of Iyer, ‘stand everything he took for granted on its head.’