Land proprietorship in Kerala is classified under three broad no-need-to-quantify heads: muttam (yard), parambu (farm) and estate (estate). The lack of need to quantify arises from an everyday fact – nobody gives out actual figures and everyone assigns everyone else acreage inversely proportional to the degree of familiarity. And everyone is happy: while the meagre holders bask under the enhanced share – of property and thereby social standing, it helps the muthalali, the big fish, hide from taxmen, credit-seeking relatives and of late, extortionists and kidnappers.

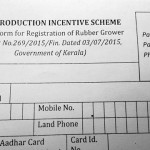

The recently announced rubber subsidy by the government mars this happy ecosystem as it requires applicants to reveal their titles to the t – possibly a reason for the dismal farmer response to the Rs 300 crore bailout package. Not to say it is bereft of political criticism (‘a panchayat election gimmick’) and general detractor tirade over the need to navigate through a seemingly labyrinthine process of uploading bills and other fiscal and commerce data after dedicated log in. The drop-down boxes in the dummy site evoked as much comprehension and interest as sari pleats. Whatever, the announcement of the minimum support price of Rs 150 per kilogram saw everyone scampering for a sliver of this relief. Including me.

In Kerala on holidays which got extended on account of losing out an assignment, I decided to pursue the subsidy ardently. Armed with information gleaned from newspapers and rubber-dealing friends (many of whom were understandably still in bed at 11 in the morning) and encouragement from neighbours and general well-wishers (the last lot my parents actually who, with an eerie sense of foreboding found only in parents, told me to check out a new movie instead) I set out on an adventure rendered Homeric by a two hundred and twenty seven organisations and offices related to rubber, a confounding insistence on part of my fellow natives in answering my Malayalam queries in English, Hindi even, an inclement monsoon and a disobedient mundu that kept de-knotting itself and flopping down.

Information. My analyses follow in italics.

The subsidy is limited to produce from two hectares. I am eligible.

The subsidy is applicable only to those with five hectares or less. I am still eligible.

There are around 12 lakh farmers engaged in rubber cultivation in Kerala. I must hurry.

The earmarked funds are enough to support just a quarter of the state’s total produce. I must really hurry.

In areas not covered under rubber producers’ societies (RPS), the planter could register through cooperative societies or service cooperative banks. The key to registration must be a form. My first stop was thus the service coop bank to where money used to be debited once the dry rubber content of the latex we sold was determined. For the past two years accruals into the account have been like an amoebic reproduction – the growth in numbers the effect of nothing extraneous.

An orange-coloured building with a wide portico and a single room office, there was ‘bank’ written thoughtfully above the sole entrance. A fair price store next door remained cheerfully shuttered. Dusty stacks of files piled up in old wooden shelves that lined the wall; when the transaction details of the last few years were handed to me as an e-copy I was floored. In the air hung a camaraderie found only between those on the same sinking boat. A ready-to-smile guy picking on a keypad nodded me to a chair.

“We don’t give forms here,” I was informed cheerfully, apologetically. Tea glasses were strewn all over, some still had tea in them, all had houseflies moving in staccato along the rims.

“Would you like some tea?”

“I just ate breakfast.”

“Maybe you should try your latex collection depot.”

Government and cooperative jobs are hugely sought-after in Kerala being sinecures and safety nets immune to agricultural upheavals like the one we were going through now. The manager of the depot had gone to Kottayam, 30 km away, on an official visit. He would be back with more information on how to avail the subsidy. Till then I could join the hearty country-talk that dissected issues from building apiaries to complement rubber incomes to the strings attached to central government loans. The discussions were so animated and genuinely interesting I nearly forgot what I was there for.

“We don’t give forms here,” the assistant manager said later. He was sadder seeing me leave the group discussion than at his inability to help.

“Try the rubber marketing office.”

Probably portending the outcome were hundreds of empty, desolate barrels I noticed only as I headed out – piled up like the triangular acrobatic formations during Republic Day celebrations in Delhi.

Even if you are going around in circles after a while each step feels like a definite progress from the last, bringing you a step closer to goal. By now I had an inkling of what I was into – I should have listened to my folks and gotten in for Premam, the highest grossing Malayalam film of the year. But while at the marketing office I actually felt glad at having embarked on the subsidy-seeking journey. A modest library with mildewed tomes welcomed me as I stepped inside the spacious, sunlit interiors – borrowed old and the uncertain new, in the words of Teju Cole.

By now I had begun to eagerly look forward to learn where to go next; getting the form itself had begun to take on the contours of a sublime act I was unworthy of. I remember feeling happy when the marketing chairman directed me to the rubber board office. Going by the sound of it things were definitely getting bigger; it didn’t matter whether I was getting any closer.

An affable (same boat?) guy took me through the dummy website the government was setting up for the purpose of subsidy disbursal. He took immense pride at the creation and beamed as one drop-down led to a dozen others as if bidding me to applaud. He showed me where to upload the bills and how to log in. He told me what details to fill. Then in the typical pedagogical idiosyncrasy, hallmark of a Keralite, he went through it all over again. And again.

A colleague called out to him lunch hour. Before he left he gave me the number of a person, some bank president, who would tell me where to get the form. This bank president, I was assured, was a puli or tiger, who knew everything I’d ever want to know.

Raring at the opportunity to meet the tiger I bounced down the stairs of the rubber board office where I bumped into an old acquaintance. After exchanging pleasantries and catching up I told him what I was doing there.

“See that photostat shop over there?” He asked pointing across the street. “You’ll get your form from there.”

I must have looked visibly crestfallen at the turn of events.

“It is just two rupees per form,” he said.

Now I felt like crying.

Footnote: The figure in today’s newspaper (July 31, 2015) peg the total number applied so far at close to 50,000; half of them have been approved. Instead of wasting my time writing this I should’ve filled up the form.

This is hilarious – been chortling since! With due respect to subsidy-needing farmers, of course.

Thank you! For both – the laff and the love. 🙂

Nice post about cultivate in rubber. Everyone need to Fill the form.

No kidding!