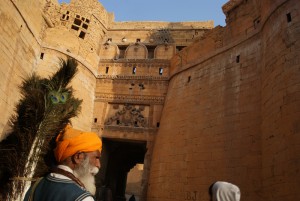

The Jaisalmer Fort stands out like a golden mirage – it is spellbinding by its sheer magnitude and imposing architecture. But once inside you feel like the subjects are running the country within its fortified ramparts and the royalty is in hiding

The Jaisalmer Fort stands out like a golden mirage – it is spellbinding by its sheer magnitude and imposing architecture. But once inside you feel like the subjects are running the country within its fortified ramparts and the royalty is in hiding

‘One of the few living forts in India,’ announced a brochure, the taxi driver, the hotel manager and finally the tourist guide at the entrance to the Jaisalmer Fort, in the exact order. All the while I could imagine the sandstone ramparts sucking in oxygen and breathing out through the many golden-coloured stately minarets. It turned out that my imagination wasn’t that far removed either: with the kitchens of countless living quarters aligned haphazardly with towering palace walls, the belching smoke and clatter of cooking vessels did indeed make the fort look and sound like a brown monster squirming under a gastronomic misadventure.

With a colourful history in stark contrast to a sepia-toned landscape, drama and deceit was as staple as romance and gallantry. The lineage of the Jaisalmer royals begins with Deoraj, a Bhati prince of the 9th century, as does the title ‘Rawal’ meaning ‘of royal descend’. On his wedding day Deoraj’s father along with1,000 attendants were massacred; the vengeful prince fled with help from a Brahmin priest. Deoraj later captured a Rajput stronghold Ludrawa, 15 km from Jaisalmer town, and made it his capital. Ludrawa with a windblown Jain temple is the first stop for tourists who head out towards the desert. A portly caretaker swatting flies at the entrance makes sure that you remove your footwear and you pay an unfair amount to take photographs of a rather unimposing structure. A young priest goes about his daily supplications with a meticulous unease, one eye on us.

With a colourful history in stark contrast to a sepia-toned landscape, drama and deceit was as staple as romance and gallantry. The lineage of the Jaisalmer royals begins with Deoraj, a Bhati prince of the 9th century, as does the title ‘Rawal’ meaning ‘of royal descend’. On his wedding day Deoraj’s father along with1,000 attendants were massacred; the vengeful prince fled with help from a Brahmin priest. Deoraj later captured a Rajput stronghold Ludrawa, 15 km from Jaisalmer town, and made it his capital. Ludrawa with a windblown Jain temple is the first stop for tourists who head out towards the desert. A portly caretaker swatting flies at the entrance makes sure that you remove your footwear and you pay an unfair amount to take photographs of a rather unimposing structure. A young priest goes about his daily supplications with a meticulous unease, one eye on us.

The Jaisalmer Fort is named after the Bhati ruler Jaisal, the scorned eldest son of the ruler, whose right to the throne of Ludrawa was overlooked in favour of a younger half brother. Not one to give up so easy he joined hands with a marauder cum invader from Afghanistan, Shihabuddin. The deal was that Shihabuddin could plunder and ransack the city for three days and take with him anybody and anything he could lay his hands on. After the Afghan left, with brimming coffers and overloaded caravans, Jaisal took over the reins with a peculiar delight reserved only for those who revel in ruling over a clutch of ruined houses and bleeding people. Nevertheless, he built the gargantuan mud fort and established a new capital and named it all after himself – Jaisalmer. The yellow sandstone fort has a fortification wall which is three metres thick, the top of which has gun holes – apparently Jaisal was never at peace with his power. Construction was quickly completed; the foundation stone was laid in 1156 AD and completed in just seven years.

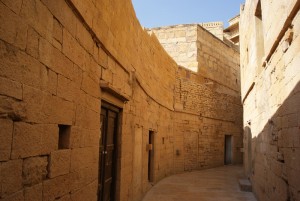

Is there an assassin hiding just round the corner? Did I see a glint of his dagger on the filigree shadow? Immerse yourself in history and you can really live the period fuelled of course by a robust imagination. Still, these thoughts could have at some point passed through the mind of the Rawal as he walked the numerous winding alleys with his hands folded behind him on his way to meet the queen in ‘Patwon ki Haveli’ – the five-storied haveli. This is the most elaborately done of the kingly quarters with remnants of elaborate murals, paintings and mirror work. Yet another prominent figure among the Rawals was Akhai Singh, during whose rule the people from around town came to settle in the slope around the Fort and started living in clusters or groups, called mohallas, named after their professions. What ruler would allow that, you wonder, especially as the Fort itself stands at a height of a mere 50 metres over the city – if not for safety, for exclusivity at least. This, as it turned out, was the beginning of the fort becoming a ‘living’ one. Today, no amount of persuasion or threats of penalising can drive out those who have made these stately stanchions their home.

Is there an assassin hiding just round the corner? Did I see a glint of his dagger on the filigree shadow? Immerse yourself in history and you can really live the period fuelled of course by a robust imagination. Still, these thoughts could have at some point passed through the mind of the Rawal as he walked the numerous winding alleys with his hands folded behind him on his way to meet the queen in ‘Patwon ki Haveli’ – the five-storied haveli. This is the most elaborately done of the kingly quarters with remnants of elaborate murals, paintings and mirror work. Yet another prominent figure among the Rawals was Akhai Singh, during whose rule the people from around town came to settle in the slope around the Fort and started living in clusters or groups, called mohallas, named after their professions. What ruler would allow that, you wonder, especially as the Fort itself stands at a height of a mere 50 metres over the city – if not for safety, for exclusivity at least. This, as it turned out, was the beginning of the fort becoming a ‘living’ one. Today, no amount of persuasion or threats of penalising can drive out those who have made these stately stanchions their home.

When somebody tells you the Deogarh is a ‘fighting fort’ you will understand why soon as you see it: the near-squeeze entrances, the gazillion steps leading to nowhere and the confusing corridors with myriad twists and turns. But how or what would make one a ‘living’ one? You look at Jaisalmer and you are still confounded. The only reason you can possibly think of is Ajit Bhawan in Jodhpur, India’s first heritage hotel. Most of the glorious forts and palaces that literally dotted the Rajasthan landscape were lying in ruins – both an emotional and financial embarrassment to the blue bloods. Once Ajit Bhawan opened its doors to the heritage-hungry public, the Umaid Bhawan, Lake Palace, Rawla Narlai, all took cue. They all offer a slice of the royal life – replete with usually an amiable Maharaja with a still-loyal coterie of subjects and manservants. Jaisalmer does it too, okay at least, tries real hard. But without the Maharaja, semblance of luxury or trappings of any sort of grandeur. To see how the Rawals lived, you have visit the museum. It has a huge collection of bows, arrows and other arsenal, currencies, the queen’s bed, the throne and a very interesting family tree. A couple of clan-heads have claimed to be descendants of Lord Krishna and one – the Ruler of Bharatpur – to the exact number – 78th.

When somebody tells you the Deogarh is a ‘fighting fort’ you will understand why soon as you see it: the near-squeeze entrances, the gazillion steps leading to nowhere and the confusing corridors with myriad twists and turns. But how or what would make one a ‘living’ one? You look at Jaisalmer and you are still confounded. The only reason you can possibly think of is Ajit Bhawan in Jodhpur, India’s first heritage hotel. Most of the glorious forts and palaces that literally dotted the Rajasthan landscape were lying in ruins – both an emotional and financial embarrassment to the blue bloods. Once Ajit Bhawan opened its doors to the heritage-hungry public, the Umaid Bhawan, Lake Palace, Rawla Narlai, all took cue. They all offer a slice of the royal life – replete with usually an amiable Maharaja with a still-loyal coterie of subjects and manservants. Jaisalmer does it too, okay at least, tries real hard. But without the Maharaja, semblance of luxury or trappings of any sort of grandeur. To see how the Rawals lived, you have visit the museum. It has a huge collection of bows, arrows and other arsenal, currencies, the queen’s bed, the throne and a very interesting family tree. A couple of clan-heads have claimed to be descendants of Lord Krishna and one – the Ruler of Bharatpur – to the exact number – 78th.

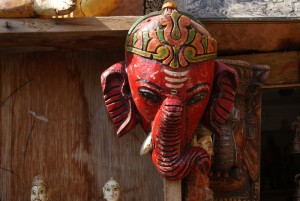

Jaisalmer flaunts its Jain heritage with immense pride and at the same time take advantage of it too, in equal measure. You will find inside the Fort some marvellous temples from the 12th and 15th centuries; the only dampener being the overt commercialisation; with a price tag for even taking your mobile phone inside. Without blinking you can interpose the signage at the entrance ‘Jaina Group of Temples’ with ‘Jaina Group of Hotels’ and onion-free masala dosas starting at Rs 30. The shops are a riot of colours – selling beaded necklaces, sequinned dresses and picture frames, puppets, gods in all sizes (thanks to tourist tastes, there is a distinct preference for the elephant god Ganesha) and cigarettes from Marlboro to Win and Paris. (No, no Gold Flake or Classic. “Sir, we prefer dollars to rupees.”) Don’t be shocked if every second house sports ‘authentic Italian’ or even ‘Israeli’ food; the saving grace is that omelettes can usually not go wrong. Even pancakes are a risk – as I learnt the hard way.

Jaisalmer flaunts its Jain heritage with immense pride and at the same time take advantage of it too, in equal measure. You will find inside the Fort some marvellous temples from the 12th and 15th centuries; the only dampener being the overt commercialisation; with a price tag for even taking your mobile phone inside. Without blinking you can interpose the signage at the entrance ‘Jaina Group of Temples’ with ‘Jaina Group of Hotels’ and onion-free masala dosas starting at Rs 30. The shops are a riot of colours – selling beaded necklaces, sequinned dresses and picture frames, puppets, gods in all sizes (thanks to tourist tastes, there is a distinct preference for the elephant god Ganesha) and cigarettes from Marlboro to Win and Paris. (No, no Gold Flake or Classic. “Sir, we prefer dollars to rupees.”) Don’t be shocked if every second house sports ‘authentic Italian’ or even ‘Israeli’ food; the saving grace is that omelettes can usually not go wrong. Even pancakes are a risk – as I learnt the hard way.

Haggling with the peddlers and jostling with the tourists, finally as you weave your way out, you feel like getting out of a time machine that took you five centuries back. An old world charm that had permeated the air, just refuses to let go. As you turn about for that one last longing look which changes it all, you are transfixed like Lot’s wife: the pile of plastic and other rubbish that streaks down the sides of this ‘golden fort’ makes you wish this fort was rather ‘dead’ and not ‘living’. The only upside to this unscrupulous littering was that Deoraj could sleep in peace – the enemy would either slip and fall or incapacitate himself over all the plastic and broken bottles.