In the beginning there was the Bastar Palace. Jagdalpur town was originally the living quarters of the palace personnel who settled in the imperial whereabouts. Sure enough it soon began straggling in all directions and today it goes a very long way in all directions. When you exit the city towards Sukma – deeper south – for the Kanger Valley it is evident that it is still lugubriously lugging along. Take the Gidam Road (NH 16) through which Jagdalpur goes on in fits and spurts till Kesulur, 12 km away. Traffic seems to abate now and the precariously stacked rectangular highrises, windowless on the two broader sides, fall off. Turn right from the junction at Kesulur toward Sukma (90 km, NH 30). Continue the good ride for another 10 km before the highway tapers to a single lane, sort of unceremoniously. The road winds up through a series of loops; cabs and small private buses ferrying domestic tourists and students on annual tours bear down this route, though with horns blaring. You reach a junction where there are vehicles parked by the road waiting to buy entry tickets to the national park attractions. The way to Tirathgarh Falls is to the right, caves to the left. It is suggested you visit the caves before it gets crowded – around noon – especially on weekends.

From the entry barrier, 10 km of un-tarred road with speed-breakers to boot almost every kilometre leads to the parking of Kutumsar Caves. The undulating paddy fields that flanked the road till now are replaced by dense sal and teak forests. The last couple of kilometres could pass for a challenging stretch from a rally course: a series of twists and steep turns which lands finally in a clearing which is the parking area. Local women selling wild berries and biscuits and packaged water squat in between rows of cars and two-wheelers. Kids scurry about between the parked vehicles and vendors. The public urinal has become a cesspool with bulky fluorescent gnats buzzing about like low-flying drones; everyone makes a beeline for the trees. Large mats have been laid out with towering tiffin carriers holding it against the wind.

The Kanger Valley National Park is one of the prime tourist destinations from Jagdalpur. But unlike the other national parks of Chhattisgarh, the main attraction is not another wildlife safari but here you enter karst country. Kutumsar, Kailash and Dandak are the three main caves in Kanger Valley of which only the first one is open to public. The Tirathgarh Falls is nearby – a good place to cool off or wash away all the underground grime and sweat. Many you meet at the caves will be here already taking a dip in the shallow waters near the plunge pool.

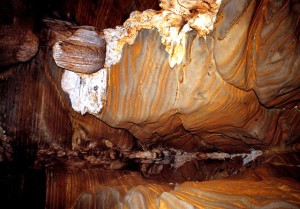

Kutumsar and Tirathgarh are very popular in the domestic tourism circuit and weekends are packed. The locals manning the cave entrance allow tourists inside only in small groups to avoid congestion – the entry is through a narrow, winding staircase which can barely fit a fully grown adult. You have to wedge and wriggle your way down. But once down there, it is dripstone cathedral. The caves were discovered in 1900 and have since then enthralled spelunking enthusiasts with its striking speleothems carved out of the dark, drippy silences. Alright, this is not caving in its real adventurous sense – you won’t be requiring karabiners or helmets, ropes or slings for abseiling. However a head torch would be handy here. Even though the passages are lit by bulbs powered by a domestic capacity gen set that purrs away by the entrance (there is even a ‘lighting fee’ included in your entry charges!) you could enjoy the limestone formations better, at your own pace more importantly, if you have your own flashlight. The rift widens as you climb lower and you are required to keep moving – twisting down, actually – till you reach level ground below so that you don’t hold up those behind. Move to the side, wait a bit and let everyone pass. Explore the ‘drip-water architecture’ of the cavernous cave on your own.

The imposing stalactites and stalagmites are formed over thousands of years as a result of the action of rainwater on limestone. Most of the stalactites and stalagmites are found in limestone caves which are in turn composed mostly of calcite commonly found in sedimentary rocks. Limestone, incidentally, makes up around 10 per cent of all sedimentary rocks in the world. Rainwater, as it falls, absorbs carbon dioxide from the air and the dissolved calcite from the rocks as it flows over them. It is this dissolved calcite that sediments once the water flows through the cracks of the cave’s roof. As water continues to drip, the size of the calcite sediment grows. The rate of growth is not more than an inch over the span of a century. What you see around are the result of accretions over tens of thousands of years.

The traversable length of Kutumsar is 330 metres at the end of which there is a shrine. Along the way there are some short detours you could take – though not encouraged by the local ‘cave minders’ – which will give you a better feel how it is to be in karst country. One path climbs up about 25 feet over wet rocks with low overhanging. Get a good purchase – you will have to clamber up on all fours and watch your head as you go higher. Both the surfaces, above and beneath, gleam a moist and shiny veneer under the light. You reach a seemingly dead end with an inviting fissure egging you on. Such intriguing labyrinths are everywhere and it is a shame that they are kept out of bounds. Just before you reach the end of the trail, you pass through a high chamber, speckled with stalactites drooping to almost head level. The ground is otherwise even.

You will be by now discovered by a local lad in charge of cave security. Just say you lost your way.

Stalactite and stalagmite: ‘Stalactite’ and ‘stalagmite’ are almost always used together that they have come to lose a very important distinction. Both words originated from the Greek word ‘stalassein’ which means ‘to drip.’ This is apt as both the formations are the outcome of rain water dripping over rocks. The difference between the two is that while stalactites are the formations that hang down from the ceilings of caves, like icicles, stalagmites grow up from the ground. Stalagmites, while being formed from the same drip-water source that formed the stalactite above it, are usually of thicker proportions.

Top tip: Stay away from the Kutumsar on weekends when the queue at the entrance can take anywhere up to three hours. You also won’t get the quiet to enjoy the vast, imposing silence once you are in the wonder/underland. Park timings: 8 AM to 3 PM (November to June); Car entry: Rs 50; Ticket: Rs 50 (Indian), Rs 150 (foreigners)

This is largely an excerpt from ‘Experience Chhattisgarh on the road‘ written and photographed by me for the Times Book Group. November to February is the best time to visit this central Indian state which is torrid and humid rest of the year. All photographs are from inside the Kutumsar Caves, those without the Wanderink logo are courtesy of the Chhattisgarh Tourism Board.

Can’t believe this place is in India – a hidden gem! Thanks for sharing.

You are most welcome. India…incredible!