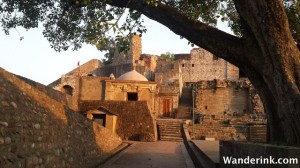

The unassailable often ends up the most assaulted. Ironically axiomatic, albeit, a historical truism. The ramparts are impregnable for the treasury must be laden. Or the courtly houris most desirable. Both accepted spoils of battle. ‘Whoever holds the fort holds the land’ goes an old Kangra saying. This made the Kangra Fort, despite its formidable layout – built atop a hill at the confluence of two rivers – and virtually impenetrable ramparts – rising like limestone outcrops from the escarpment, in some places up to 300 feet – among the most besieged forts in the country. The women – as mountain folks are generally – were most charming and the gold was boundless; one account of an attack by Mahmud of Ghazni records carting away of around a million gold coins and over 20 tons of gold and silverware by the pillaging army. Despite unrelenting efforts of marauding armies from the days of Alexander the Great, including 52 futile attempts by the Mughals alone before Jahangir’s successful invasion in the 17th century, what we see of the fort today – the ashlars scattered in the enceinte, the crumbled corbels and ancient temples razed to rubbles – are the remnants of the horrific earthquake that hit Kangra in 1905.

Kangra Fort is 25 km short of Dharamshala if you are driving from Delhi; Dharamshala itself is around 500 km; a good eight hours on the road. So by the time you reach Kangra chances are that the fort will look like an extended craggy motte from the distance, in the fading light. The anticipated rendezvous might tempt you to floor it, hit Dharamshala or Macleod Ganj and cosy up ASAP in the heavens, under the stars. But do make the slightly protean detour to the ruins – a heritage dirge but an archaeological gem, a historical caterwaul but an apotheosis of human fortitude – both of the vanquished and the valiant. For strategic reasons, the fort is built on a narrow strip of land between the Ban Ganga, a tributary of the Beas River, and the Majhi River, and can be accessed only from the land side which leads to the town. It’s better to ask for the route as the signboards are either peeling off or non-existent. There are several hairpin bends flanked by residential or commercial buildings. Be on the lookout while coming down as at some point the road bifurcates for one-way traffic – marked again by an obscure warning.

Each of the conquerors left their lasting impressions on the fort via the darwazas, gates, or more specifically, grand entrances. (A descendant of the Katoch dynasty – who built the fort – reminisces in the audio tour what his grandfather told him: Never enter the gates head first as it accords the hidden enemy a clean swipe at your top. There are 11 darwazas in the fort today giving one enough practice at self-preservation.) The many gates as well as the long-winded, sharp-turning narrow passages were a safety feature standard of forts. The main entry to the fort is through a narrow pathway which takes one through the Ahani and Amiri Gates before some sharp bends lead to the Jahangiri Gate. The Jahangiri Gate leads to the Andheri Darwaza (‘gate of darkness’); here the path splits in two – the left one leading to the Darsani Darwaza which opens to the courtyard with the remains of the temples of Lakshmi Narayan Sitala. Though this temple was devastated in the earthquake of 1905 some enthrallingly elaborate stone carvings depicting shrines, garba grihas or inner sanctum and goddesses still abound. Across the ancient temple ruins there is a more recent temple devoted to Ambika Devi, the royal family deity, with a priest who performs pujas and chants devotional hymns to the whir of a table fan. There are also the remains of a Jain temple with one of the earliest known statues of Mahavira, the last tirthankara (a saint in Jainism). Though the remains feature ornate lintels, elaborate plinths and a medley of some of the finest rock cut sculptures and motifs of Jainism, it is in need of some serious conservation.

From the temple courtyard, another narrow passageway takes you to the topmost level of the fort from where the view of the Kangra Valley is spectacular. There is a donjon from where sentries would have kept an eye out for enemies trying to scale the near-vertical walls; murder holes await signal to pour boiling oil down on anyone who breaches bastion. Today the most exciting sight would be peering down the vertiginous heights, the eagles swooping down with a whoosh and the occasional chug-chugging past of the Kangra Valley toy train. Traversing a total of 162 kilometres from Pathankot to Joginder Nagar, the train passes through numerous bridges and streams and is serenaded by the glorious Dhauladhar range through most part of the journey. The little blue-and-white train meandering single-mindedly like roosting bovine through expansive fields across the butte, tracing a path amidst dwellings and chimneys spewing smoke looks almost like a countryside fixture.

The remains of a mosque, peacefully ensconced within a lush thicket, believed to have been built by Jahangir are a throwback to the days when the fort was the gateway to the entire valley. Way before Jahangir conquered the fort – and the women of the court jumped into a deep well inside the palace grounds – the Katoch clan had a face-off with the Grecian Alexander on the banks of the Jhelum in 326 BC followed by skirmishes with King Ashoka. Mahmud of Ghazni wiped out the treasury during an 11th century raid; Mohammed Tughlaq and his successor Firoz Shah both captured the fort during 14th century but couldn’t hold on to it for long. By 16th century it was the turn of Akbar followed by son Jahangir to hold sway. Though by 18th century the Katochs had regained some control over their land, it became the turn of the Gurkhas of nearby Garhwal to show interest. For thwarting their overtures, the Katoch ruler Sansar Chand sought help of Sikh ruler Ranjeet Singh who would ask for, what else, but the Kangra Fort! The fort remained in the hands of Sikh rulers till it was handed over to the British in 1846 as per the Anglo-Sikh treaty.

‘Kangra’ or ‘Kangra Valley’ denotes an entire region with the majestic Dhauladhar range of the Himalayas to the north and a bunch of undulating massifs to the south. It is thus a strip of land roughly about 150 km in length and 50 km broad with an amazing vista on both sides.

Who wouldn’t want to lord over this territory!

I was there… it is a strategically located and well built fort