Before the ‘make in India’ clarion call there was the original made in India, the jugaad. Variously described as a ‘hacked up improvisation’ or ‘frugal and flexible approach to innovation’ this is the desi avatar of the denim-clad DIY. Some of these frugality-fuelled approaches to sorting everyday problems – which abound in Indian hinterlands – are literally jaw-dropping.

In Punjab I saw two-wheelers of all makes wildly mutated into water pumps; only the Bullet motorcycle was spared from the agrarian outing for reasons some attribute to impossibly Freudian. There were many takers for the old Chetak and Vespa scooters who squeezed the superannuated warhorses out as juicers. In Rajasthan a whacky vendor had painted the name and establishment year of his lassi bhandar over a rickety washing machine – which was the lassi bhandar. Not all have to come with churning power. I have watched delirious portly guys wading bravely into the lashing seas of Puri with nothing much more than a few empty litre cola bottles strung around their waist. It’s a buoy! I exulted. The water-filled plastic pouches which hung from the ceiling in a tea stall in Billing, HP, apparently bedazzled gnats away. And of course, there is The Jugaad itself juddering along, spewing and sputtering all around you as soon as you cross the eastern borders of Delhi into UP: generators, water pumps, washing machines, Jughead’s digestive system…anything with an industrious swirl born again with the visceral addition of a few belts and bottles into a specious but spacious people transporter. The driver, if lucky, gets to sit on a plastic bathroom stool; mostly he just stands with the rest of his fares as sanding also means more room.

“How did you learn to drive this?” I once asked a driver, gushing forth admiration. It was a diesel water pump which ran on kerosene piped in directly from a sooty canister, bottle caps doubled as knobs.

“What’s there to learn?” He asked with a shrug. “I only made this.”

He got an admirer for life.

“What’s this toothbrush doing here?” I asked, pointing to one sticking out of a circular hollow which could’ve been the speedo discernible only to the bucolic eye. It could be to flick the trip metre when he left home.

He blew a raspberry at the pathetic urbanite’s negligence.

“Oh, that’s where I leave it after brushing my teeth.”

I still remain a life-long admirer.

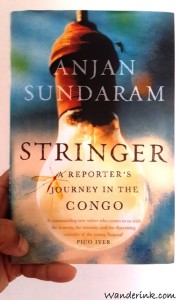

Reportage as travelogue: Stringer

When Tony Wheeler said that democracy is most likely to be missing from a country with a ‘democratic’ prefix, he was talking about the Congo. Well, the Democratic Republic of Congo. Congo has variously been described as ‘Africa’s heart of darkness,’ ‘Mobutu’s kleptocracy,’ and site of massive massacres and rapes. But most of it rarely make it to the front pages of newspapers that are delivered to our doors; they are instead relegated to a couple of columns under an ‘international news’ header buried somewhere between the editorial and sports pages. Commercial pressures have forced the media to turn its gaze towards news that boost circulation – often inane, shallow stories that contribute to the reality dumbing down has become today. Horizons are shrunk in popular reporting and advertorials have been guilelessly revamped as ‘paid for news.’ The Congo picture has been thus compressed or faded out to make way for news that keeps the government and the corporates in good humour. Two wars have been fought in this resource-laden nation since 1996, wars that have left over five million dead.

It is into this Congo that Anjan Sundaram arrives ‘at 22, on a one-way ticket, without a job or any promise of publication, with only a little money in my pocket and a conviction that what I would witness should be news.’ He manages to score a lowly-paid stringer post with Associated Press and begins to share living quarters with a family in the restive slums of Victoire with a ‘reputation for gangs and disorder’ in capital Kinshasa. His ‘Stringer: A reporter’s journey in the Congo’ chronicles the lurid events and little joys over the course of his year-and-half stay in Congo as well as some shockingly interesting asides like pursuing a story about a pygmy chief who sold the logging rights of his land for bags of salt. Many episodes and characters in the book resonated with the people and events during my own stay in neighbouring Nigeria several years ago: the zeal of Corinthian the preacher, casual attempts at seduction by Fannie and Frida and quite chillingly, the kidnap and robbery – my dad was driven around Victoria Island by two armed men who relieved him of the gratuity money.

It is into this Congo that Anjan Sundaram arrives ‘at 22, on a one-way ticket, without a job or any promise of publication, with only a little money in my pocket and a conviction that what I would witness should be news.’ He manages to score a lowly-paid stringer post with Associated Press and begins to share living quarters with a family in the restive slums of Victoire with a ‘reputation for gangs and disorder’ in capital Kinshasa. His ‘Stringer: A reporter’s journey in the Congo’ chronicles the lurid events and little joys over the course of his year-and-half stay in Congo as well as some shockingly interesting asides like pursuing a story about a pygmy chief who sold the logging rights of his land for bags of salt. Many episodes and characters in the book resonated with the people and events during my own stay in neighbouring Nigeria several years ago: the zeal of Corinthian the preacher, casual attempts at seduction by Fannie and Frida and quite chillingly, the kidnap and robbery – my dad was driven around Victoria Island by two armed men who relieved him of the gratuity money.

In ‘Stringer’ Anjan assiduously if inadvertently brings out the need to immerse oneself in a land however abundant it might be in material to bring out its true essence, the right perspective. In a piece he wrote for The Guardian, the author crosses swords with news organisations ‘which tell us that immersive reporting is prohibitively expensive’ who ‘parachute (reporters) in with little context.’ It is also replete with poignant moments of a reporters’ dilemma: ‘Death as a rule, had the best chance of making the news. And in a country torn by war one might imagine such news would be abundant. But in Congo, so many people died that, farcically, mere death was not enough: I needed many deaths at once, or an extraordinary death.’ But it doesn’t in any way simplify the excesses – and how little we know of it – of the Congo. The democracy continues to be embattled, activists arrested, power struggles are still on for the land abundant in minerals like uranium, copper, cobalt and coltan (used in mobile phones), anti-government demonstrations are bloodily crushed.

The book brims with anecdotal observations on the country’s social, political and municipal layouts. The city which appeared as ‘a collusion of secrets only the locals shared.’ The ‘donut society’ with the family at the centre and the clan or the street forming the ring around it followed by the chaotic world. The ‘offices’ the women kept – which referred to the men they dated simultaneously till they settled on the richest (or the most cunning); numbers of which would at times go up to five. And my favourite for its black and white ubiquity: ‘Slum boys communicating with motions of their heads, in rude bursts.’ ‘Stringer’ is essentially reportage, intense and ebullient, innocent and coming of age one at that. The book is as much place as people, tale of kindness and living and peeps into history, hopes for the future – pretty much the same elements that make for great travel writing. It will be a while before Congo makes it to the ‘must see’ destinations reeled out by the usual bunch of list-compilers. But the book is a must-read for its depth of understanding and integrity of portrayal while writing about an alien land and its inhabitants.

Epley Manoeuver for driving pleasure

My folks’ month-long vacation in Delhi with me culminated with a 1500 km round trip to Shimla, Dharamshala and back – in four days! A commendable feat considering my mom once used to suffer from vertigo – a sure-shot mood-killer on winding roads and / or high speeds. But she got rid of it with the Epley Manoeuver – a series of simple gravity-aided motions for which one can either enlist a medical practitioner or do at home with some ballsy help. My mom went to a doctor, my wife used our daughter.