One late afternoon I emerged from Junagarh Fort, the city of Bikaner radiating in all directions, convinced why it was my favourite fort in the country.

- There was no out-of-the-blue cordoning off of areas with the unsettling ‘The royal family still lives here’ excuse.

- This was not a ‘living fort’ – and by extension undergarment-splattered ashlars, stinking bathroom nullahs cutting across your path, unyielding milch animals, and static squatters were missing.

- The fort itself was immaculately, passionately, preserved. (My best guess was because the erstwhile ruling family was still pretty much active in its preservation – and not given over to any government organisation.)

- The audio guide was quite comprehensive as it was exhaustive – the best I ever laid my ears on. (There was no need for a deposit even – neither money nor your travel documents!)

- The eateries were right by the exit – just where I wanted them. And when.

- Lastly but mostly the absence of severe ‘No Photography’ signs in the fabulously stacked armoury museum.

I say ‘mostly’ as I have always felt that banning photography from museums is a bit like being sent to war without Kevlar – you either run or drop dead soon enough. I have been admonished for taking pictures of stone sculptures going back to way before Christ and even Buddha at a museum in Alwar; apparently the monuments that came through numerous wars and natural calamities over thousands of years cannot take the electrons flashes emit. (Otherwise a most fabulous treasure-trove, the Alwar Museum.) A clammy hand cupped over my camera lens at an armoury museum in Jaipur miffing me no end; soon I was in the hallowed presence of the museum director. The spiel doled out to me had much to do with scallywags wanting to steal dagger designs and other cutting-edge technology of lever-action Winchesters. Museums took you back in time and some people decide to stay there.

As the second son of Maharaja Rao Jodha of Jodhpur, the only way Rao Bika could have had his own kingdom was to found one. Aided by a favourite uncle a military strategist and a few hundred infantry, he set off in 1472 on a conquest spree annexing large tracts of arid land lying towards the north of the region fringing the Thar. What was known as ‘Jungladesh’ was renamed ‘Bikaner’ after the conqueror. Though Rao Bika began constructing Junagarh six years into his reign, what one sees of the fort today was largely built by Raja Rai Singh, the sixth ruler of Bikaner (1571 – 1611). A general in Mughal Emperor Akbar’s army, Rai Singh took just four years to build it (1589 – 1593). It also helped that a pleased Akbar had rewarded him with vast jagirs (land with its revenue) for his successful military exploits. Successive rulers have added their own mahals (palaces) and courtyards, donjons and pleasure suites which all go into making Junagarh an eclectic – and a tad confusing, at times – and imposing piece of architecture.

Though not on a hill top – like forts generally are – Junagarh depends solely on its gargantuan dimensions to inspire awe. This sandstone and marble fort is built along a rectangular layout with a massive wall measuring 986 metres in length, 4.4 metres broad and 12 metres in height. There are seven gates – of which only two are the main entrances, for security reasons – and 37 bastions; a moat flanks the fort which is now dry. The main entrance is the east-facing Karan Prol (‘Prol’ is colloquial for ‘Pol’, as it is written in other forts in the north of India, and means ‘gate’) through which the kings used to enter the fort; manning the gate now are two impressive sandstone elephants with their business-meaning mahouts. From here one passes through a winding courtyard with one – just one – shop, a travel agency, sticking out like a red-sore thumb, leading to the inner gate. The ornate handprints carved onto the entrance by Daulat Prol commemorate the women who committed sati by jumping into the funeral pyres of their soldier husbands who died in battle. Like in any other fort in Rajasthan, here too they serve as a solemn reminder that you are stepping into a lot of history and intrigues, machinations and war, valour and splendour.

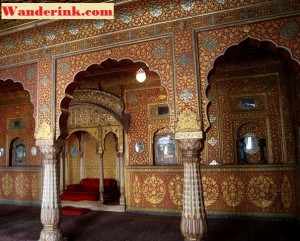

One passes at first through the marble and stucco grandeur of Karan Mahal, also the ‘Hall of Public Audience’ built by Karan Singh who ruled from 1631 to 1639. A fine amalgamation of Mughal and Rajput architectural elements the walls feature plaster works of green and gold embroidered floral motifs which are believed to have been the designs of master craftsman and artist Ali Raza whom Karan Singh met while battling the forces of Golconda. Ali Raza is also believed to have been behind the luxuriant embellishments – stucco work in gold – that dazzles Anup Mahal, a multi-storeyed structure with its own private hall of audience, a throne, an area for guests which was also a performing arena for dancers and musicians. A great patron of art and culture, Maharaja Anup Singh’s reign is regarded as the golden era of art in Bikaner. The carpet here – of Persian design – made by the prisoners of Bikaner jail still looks arresting, its hues still intact.

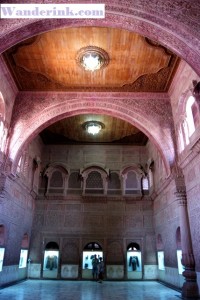

Next to the Anup Mahal is the Badal Mahal meaning ‘Cloud Palace’ with its blue cloud paintings symbolising an entire kingdom’s yearning for rain. Here one can find numerous paintings typical of the Shekhawati area which falls nearby as well as those of Lord Krishna with his consort Radha – evoking the romance of the monsoons. Gaj Mandir, the private chamber of Maharaja Gaj Singh and his two main wives weaves a world of fantasies with its golden-coloured interiors, murals, sandalwood, ivory, stained glass and numerous mirrors. The many niches and slabs one sees here would have once served as bibelots or shrines. The Gaj Mandir is also called ‘Sheesh Mahal’ meaning ‘palace of mirrors’. Dungar Niwas is named after Maharaja Dungar Singh, regarded as the father of modern Bikaner who introduced several administrative and social reforms including introducing electricity in the state. Lining the room are an array of alcoves with mirrors and pietra dura works along the wall lending the regal a touch of sublime. The Hawa Mahal or ‘palace of wind’ is where the rulers used to relax during the summer. The mirror placed above the bed has been variously ascribed purposes of pleasure and safety. Most of the coloured tiles one finds here were imported from Europe and China. The cavernous Ganga Durbar Hall designed by Sir Samuel Swinton Jacob (who also designed the nearby Lallgarh Palace where the royal family now stays) looms over you with its pink stone columns and fascinating relief carvings of deities, plants and animals. The Ganga Hall was built by Maharaja Ganga Singh, an accomplished diplomat and adventurer, shrewd military tactician and a progressive ruler who reigned from 1887 to 1943.

Weapons have always been pivotal not just in wars but also in court ceremonies and official pageants. All through history arms have occupied the apotheosis of technical and artistic capabilities of man. The collection on display at Vikram Vilas is one of the finest tributes to instruments of offence and defence one can find anywhere. Not just armouries from the dynasty, it also has a jaw-dropping collection of guns, knives, swords and other weapons of destruction from hundreds of years ago. Also featured are some interesting war souvenirs and honours conferred upon the rulers by the Mughals for merit in battle. The quirky pride of place here has been given to a De Havilland ancient which was presented to Maharaja Ganga Singh by the British government for his services during the First World War. Then, shot down machines are on display at every second cantonment area, right. So big deal! But here comes the catch: This was put together from two different DH 9s wrecks!

One more reason Junagarh tops my list.