On the day of the museum’s inauguration in January this year one of the invitees, a prominent local politician, said to Sunny’s wife Josia “This is sheer craziness.” It was, one can imagine, only in the course of faithful disbursal of his duties as a democratically elected representative of the people – the vox populi. Because that was exactly what most of those who had gathered there thought: Sunny must be off his rocker to sink his entire retirement funds into a no-return venture like a museum. Many months later, as the buzz around it grew, the general take on ‘Discs & Machines – Sunny’s Gramophone Museum’ hasn’t changed much. The reason is that here in Kerala, my home state, both status and social cohesiveness are measured in terms of financial prudence: Gratuities and pension benefits are invested wholly in chits and gold, insurances and income plans. But a little time with Sunny is all it takes for a long hard relook at age-old priorities, traditionally approbated parameters of happiness and, on a more subliminal note, probably the purpose of living itself.

“I really had to borrow more money to finish the work,” Sunny confides with a childlike enthusiasm which is quite infective. The museum – built right next door to his residence – doesn’t dazzle you with its design nor does it stagger with an opulent spread. But what it does is, besides informing one about the world of vintage records – those released between 1890 and 1960, approximately – like nowhere else in the country, there also is a moving realisation that it is the fruition of a childhood passion and the culmination of a near-Messianic pursuit to spread happiness. At least the way Sunny knows it.

Nipper listening to his master’s voice in the legendary HMV logo – an early version of which adorns the entrance to the museum – is in fact evocative of Sunny’s own earliest memories of the gramophone. “When my father used to play his records I remember walking around the gramophone wondering if someone was inside.” His father, Mathew, taught at a nearby school and Sunny remembers him coming home with a new record every other day – which would also be shared with music aficionados nearby. “If some new record was released during holidays, the peon was assigned to get a copy and deliver it to our house.”

The father’s obsession grew into a compulsion with the son: Sunny’s eventual employment with the forest department – and the fallouts with authority that ensued – ensured his posting to the farthest wooded crannies of the state. The quietude of the sylvan surrounds only served to make music further indispensible. “The first thing I would pack following a transfer order was my collection of records.” Music and records became the cornerstone which held the rest of him in place, transmitting a tranquillity which helped him put together a capacious tome on his family history. For the same Sunny even developed an ingenious indexing system – the name followed by a series of letters in upper and lower cases which spelt out the exact degrees of separation between relatives and their gender. “The life of a ranger during the 80s was much less exciting than what it is today,” he says referring to the episodes of horrendous poaching that has been wracking the state forest department recently. “On most days I could return to my quarters as dusk fell, to the embrace of my records.”

Discs

Over the years his pile of records grew into hundreds and thousands. Today it tallies at over a lakh and takes up the first floor of the museum in neatly labelled stacks. After the HMV hoarding with the forlorn Nipper there is also a signage of Odeon, leading music distributors in India once upon a time; this was one of the only two remaining boards in the country. Sunny narrates exuberant not just on the hardships endured in the procurement of his collections but also on the history behind each. Though the Deutsche Grammophon Company had produced an album in 1908 it went largely unnoticed. It was when Odeon released Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite a year later that the concept of album came to be noted by the public; popularity sought it several years later.

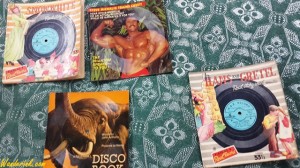

By a corner are some man-high flex standees featuring essential information which goes a long way in phonographic initiation – and exploration. As a kid though my dad had a collection of ‘vinyls’ mostly Hindi movies and English albums and some German symphonies – what I remember most vividly was my godmother twisting to Dum Maro Dum from Hare Rama, Hare Krishna. Here I was introduced to shellac, one of the earliest disc record materials, which was in vogue till the less abrasive vinyl came in the way. I was also caught agape by the sheer diversity of the shapes and sizes they came in. The smallest in the museum was five inches in diameter and the biggest was 16 – both of which I had never seen or knew existed. There were also seven and 10 inch ones, square-shaped, made of paper and of translucent vinyl. The different rpms – rotations per minute – was yet another facet of the gramophone’s technical history I was introduced to; 78 rpm which was more or less the norm till the second World War was eased out by 33 1/3 rpm popularised by Columbia Records and the 45 rpm favoured by RCA. Both had their own benefits, hence takers: The home record player, a rage in the 50s, featured three or four-speed players which could accommodate different rpms.

Emile Berliner’s seven inch discs are the oldest records in the collection; Berliner was a German immigrant in America who first patented sound recording in 1887; and I thought it was Edison all the way. Other priceless recordings from the late 19th and early 20th centuries include those of artistes like Gauhar Jaan (1902), Narayani Ammal, Coimbatore Tai, Banglore Tai, Salem Godavari, Nagaratnam, the entire works of MS Subbalakshmi and KL Saigal. Speeches made by Mahatma Gandhi in India and abroad, ‘Ab Dilli door nahin’ and other exhortation clippings of Subhash Chandra Bose, sound bytes from Sarojini Naidu and Jawaharlal Nehru’s first speech to an Independent India lend the archives a patriotic flavour.

At ‘The role of gramophones in Indian Independence movement’ talk organised at the Gramophone Museum on August 15 this year Sunny played for the audience different versions of the Vande Mataram – from the one set to tune by Tagore to a brisk version specifically for Chandra Bose’s legions, a stirring one in Bengali and a somnolent one in Tamil. Apparently the song was slated to be the national anthem till it ran into a spate of controversies including one which claimed it was actually singing paeans to the gora. Besides the evergreen Rafi and Lata, Asha and Kishore, Mukesh, Ghulam Ali and Bismillah Khan, there are also regional rarities like sound tracks of old Malayalam, Tamil, Kannada and Telugu movies and dramas. The museum – and Sunny himself – is a treasure trove of music and cinema history. “In 1915, depending on the popularity of the singer, records were sold for anywhere between Re 1 and Rs 5 – also the price of an acre of land!” Serious researchers and ‘vinyl travellers’ might soon be provided boarding and lodging within museum premises.

Machines

As you walk in through the door of the second floor hall an array of shiny and slightly subfusc metallic clutter meets your eye like the leftovers from a lorimer workshop – these are spare parts for the 250 odd gramophones arrayed here. The earliest ones date back to late 19th century and the newest are from the 80s. From portables to table tops and cabinet models, ‘at least 80 per cent’ are in perfect working order. Some of the most famous models from HMV, the Swiss-made Mikiphone considered the smallest in the world, several horn gramophones from Czechoslovakia, early portable models from Germany with the distinct front crank, toy and plastic and pencil box gramophones are all displayed in functional shelves of three rows each.

The perspicacious collector that he is, Sunny trawls the ‘chor’ and other backstreet bazaars everywhere from Delhi to Mumbai, Mangalore and Calicut for gramophones as well as discs. Besides, it also helps to have a network of ‘informants’ who will tell you of a potential windfall – an old bungalow being razed somewhere or a bored or in-need collector selling. Mannadiyar from Palakkad and Abdul Salam from Calicut have given Sunny some his most fortuitous leads. The floor also features an eclectic collection of valve radios, old tape recorder decks, wire recorders and the earliest compact disc Walkman of the 80s – which sounded the death knell of many magnificent instruments. Ancient Singer sewing machines, most of them still working, throw light on the upwardly mobile Keralite from over a century ago. In case one is missing the macabre there is an executioner’s sword made of the heaviest iron featuring a finely engraved edge.

When the politician said – only semi-jocularly – that her husband was crazy Josia replied that the world was an interesting place because of people like him. It was not a pat answer to maybe a scabrous statement but faithfully reflected where she stood in Sunny’s scheme of things – right by his side, as his friend and confidante and sometimes even lending a much needed hand with, say the cataloguing. At an Indian Association of Sound and Audio Visual Archives seminar organised in Delhi in 2012, Sunny presented a paper on the limitations of the private gramophone collector; the most debilitating of which was lack of spousal or familial understanding and support.

“I have a friend, also a fellow collector, who had to lie to his wife that he paid only Rs 300 for a rare record whereas he actually paid Rs 1000,” Sunny says. The truth would have led to a showdown which he was trying to avoid. Then like most lies this one too came at a price. “When my friend was not home the wife sold it to somebody who offered Rs 500.”

Others

Josia is just back from work; she is a senior officer at a bank in nearby Pala. We are all having garden fresh juice with home-grown bananas.

“What about the vintage cars?” I ask her probably sounding too bent on poking a hole at the mature modern day fairy tale. “What do you think of them?” There are five of them parked in makeshift garages in the front yard – an Austin from 1933, a Morris, couple of old Fiats and a Montana, which I remember was big news for the fibreglass body when I was in school – a feat quite ahead of its time, perhaps.

“Oh I like them actually,” she replied and asked “Can you imagine the consternation it caused in the countryside when one of our relatives went to church for his wedding in the Austin?” Yes I could and I could also see quite clearly where she was coming from. Sunny is obviously a very lucky guy. And he knows it.

“I still don’t know whether this is all real or I’m living in a dream,” he says. “I’m just immensely happy when I am in the midst of my gramophones and records, cars and bikes. And I hope I am able to share some of that happiness when I take people around.”

I told him what I found: Both his enthusiasm and happiness were infectious.

“Did you know that the Rajdoot GTS came to be known as ‘Rajdoot Bobby’ after it appeared in the movie Bobby?” He asked me sitting astride the motorbike which resembles a moped with muscle.

No I didn’t. Was the one next to it a Jawa?

“Yes, the precursor to the iconic Yezdi.”

As I leave I know that there are paintings and wood carvings done by Sunny which I haven’t yet seen – we both have prior appointments for which we are already late. And of course there is the well-stocked library of which I take a fleeting glance as I flee – mouldy, leather-bound oldies proudly announcing their erudition in refulgent letters.

One good thing about the singular discovery right in my own backyard – I hail from nearby Pala – is that I could always be back, for longer. Yet another was that I found it at all – we never expect to find humdingers in the humdrum of our homes.

The museum is open on weekends from 2 – 7PM; weekday entry is through prior appointment with Sunny. Call +91 8137020285. Website: www.sunnysgramophonemuseum.com. Entry is free.

How to reach: The nearest rail head is Kottayam. Pala is 30 km from here along the state highway and Plassanal, where the museum is located, is another 8 km from Pala. You pass through Bharanaganam, a Christian pilgrim centre, and in three kilometres reach Ambara from where you have to take a panchayat road to the left for a kilometre. Directions to the museum are clearly marked here.

Some exaggerations are seen!!!1) I was working in Kerala Forest Development Corporation(under Forest Department) for 36 years from April 1977 to 31-12-2012.As per a Goverment Order of 1975, we were Forest Officers.From 1977 to 1999 I had to wear uniforms similar to those in Forest Department ( with 1/2/3 stars) During the last 14 years, I was in the post of Divisional Manager(equi. ACF) and had no uniform.

2) Schools used to by books, records etc.. occasionally. So, getting records from school was occasional!

3)My early companions in service were books and cassette tapes. Since no pre-recorded tapes were available, I had many songs copied from gramophone records. Later, CDs were added.

WE Indians have not taken these endangered recordings! Last year I had made a presentation in Berlin.They even published it without editing. This month I will be on tour to Paris for a photo exhibition on the Museum in the French National Library and for a talk in Vienna in October.This shows the interest they have in this !!!Not a crazy thing for them!!!!!

Many many thanks for projecting me much beyond my figure size!!!!!

Sir, you ARE much beyond your ‘figure size’! 🙂

Names like 1)Mr. Mohamed Shafi(known as Gramophone Shafi) from Kozhikode, who comes occassionally to help me with the valve radios and record players,helped in collecting records from many locations in North India, 2) DR. Suresh Chandvankar, Secretary, Society of Indian Record Collectors, Mumbai, from whom I got the history and importance of my collection and the need for exhibiting it, 3) and my brothers who did not consider me as a crack………..

also are valuable in the formation of my museum!

Yes, Sunny commendable efforts from many people have gone into the fruition of your museum. All your associates and family and above all you deserve to be lauded! I really hope the museum gets the recognition and appreciation it truly deserves. And as I said when we met, I’ll be back for a longer pottering. Do keep in mind if you can do anything about my valve radio. Best!

If it is in bad shape we can think of a better one in working condition from Calicut.

Thank you but I want to get it mended – a lot of stuff attached to it.

News of the Museum has spread to Chennai! Crew from Tamil News Channel “Puthu thalaimurai” will be here on 14th & 15th for a coverage on the Museum!!

Congratulations, Sunny! Am very happy for recognition you’re getting. Its due!

I’m Jiji, Sunny’s youngest brother. Just wanted to contradict Sunny that we brothers do not thing of him as a crack. He really is a crack and the world need a few of such crazy people…

Hahaha! Right about the need for cracks…