To paraphrase a Victor Hugo, nothing can stop an idea whose time has come. Farmfrnd is just that – an idea most pertinent to our times. ‘The app seeks to network the farmers with local shopkeepers and end-customers by avoiding middlemen who typically hinder fair trading.’ (The Hindu, Oct 30, 2020).

From ideation to fruition, the application took almost two years. I know, it doesn’t take that long but the trip was memorable, a humungous learning. And hopefully only the beginning.

Tapioca in the trunk

‘If it weren’t for the women, guys would do nothing.’

My friend Krishnan, whom I have known for over 20 years now, told me a few days ago. We were on our usual hour-long weekly round-up; Krishnan, a corporate lawyer based in Bangalore, takes care of the legalities around my Farmfrnd app which was launched on that day – on Oct 28, 2020 – by the local MLA, popular politician and film director, Mani C. Kappen.

A strong statement and I wanted to take exception to. So while he went on, I began to think. Earlier that evening I had cut a banana bunch from a tree which had started to ripen; then it was the mother who had pointed out that owls were already holding prandial get-togethers there. Before I reverted to our discussion I realised that there was an LED bulb which I had changed a few days ago without anyone asking me to – which was only a matter of time anyway. Then I thought about the genesis of the app itself a couple of years ago. My mother and I went around our hometown Palai with 70 kg of tapioca in the car trunk to find a buyer. It was Christmastime and I had just landed from Delhi where I work; mom assured me they were all waiting eagerly for me. Before long I realised that by ‘they’ she meant a tidy heap of freshly dug sinuous, tapering roots.

Thus began our adventure to find a shop which would buy our ware. I counted 12 outlet owners who shook their heads with genuine anguish and apology ‘who eats kappa (Malayalam for tapioca) in this season of cakes?’ and some who couldn’t be bothered to even look up from their busy cash registries while shaking their heads. Since hopping in and out of the passenger seat was cumbersome for my 70-plus year old mother, the onus of making the sales spiel was on me which anyway didn’t last very long. I got the twice over at a few places as if scrutinising me for hidden prank cameras or I had offered them home-grown weed on the side. To be fair, I was a new face in a well-oiled scenario. Forget the shops, in town even I was a stranger having left some 25 years ago. Two or three vendors who remembered me were more curious about my wife and kids and got only curiouser when I told them I was bereft of either. Instead of pointing me towards a shop where I could unload my stuff and repair home for the holidays, they told me about marriage brokers and fertility specialists they were sure could help.

It was then it occurred to me that while the bigger farmers had their marketing ties ups in place, the smaller ones lagged. But this was strictly not an injustice as the shopkeepers could count on the big farmers to deliver a specific produce at a given time while the smaller landholders kept experimenting with their farming depending on their own needs. Still, it didn’t mean they had to gad about town, across scores of shops, a looming uncertainty. The output was of the same quality, if not better, considering the small farmers grew largely organic. The quaesitum had to be this awareness, accessibility and the ability to connect as per requirement. Altogether making the most of your farming output and develop some valuable relationships while at it.

Finally, we managed to find a buyer in the 15th or 20th shop along the outskirts of town. Instead of being ecstatic, I was grumpy.

“Shall we go home now?” I asked the mother, testily.

“Wasn’t it you who told me about the KFC guy, some colonel type, some time ago?” She asked pointedly. “How many did he meet with his recipe? A thousand?”

I ignored her.

To the info park in Kakkanad, Kochi

For the past few years, my work as filmmaker documenting the corporate social responsibility work of a multi-interest conglomerate has been bringing me to Kerala every month. Besides the work of course, I was in love with the place the company is situated – Kizhakkambalam, a lush, water-laden purlieu of Kochi. My fortnight each month was spent at the company guesthouse overlooking a paddy field where storks rode grazing buffaloes like they owned them. The landscape was so becalming that even when they pecked at the bovine bottoms, nobody flinched. Instead of the dining table, I would stand by the side of this georgic serenity and have a leisurely breakfast before starting for office. The company itself did a lot of work promoting farming, fishing and agriculture related activities like building endless kilometres of canals and reviving old ponds. One of my favourite pastimes was flying my drone camera over the village to see the copses next to little lakes and different shades of green that radiated all around.

Interestingly, the over 250 acres of glistening metallic domes and high-rises, the info park in Kakkanad, was just a few kilometres from this arcadia. After the shop-hunting in December the previous year, I had outlined the idea for Farmfrnd by early 2019, sounded off Krishnan and a few others in the tech space and was assured the idea had merit. Krishnan and I met a few developers in person before zeroing in on Arun and his gang at Infintor based in Kakkanad.

It was the first time I was venturing into Kakkanad ever since its development into an IT hub during early 2000s. The drive from Kizhakkambalam doesn’t quite prepare you for what’s in store – winding roads that ramble around lakes and paddy fields, up and down erstwhile knolls, blinks through little junctions with a bakery or a grocery shop, finally pauses atop a narrow stretch with tall building choking it from both sides to reveal towering concrete structures arrayed to impress investors and lure them to the special economic zone. Companies itself were in a constant state of flux – shifting out, moving in, shutting down or reopening with trimmed manpower but vision and enthusiasm intact. The sluggish economy announced itself across many deserted hallways and closed down office spaces, largely empty parking lots and that lone coffee machine trying to look perky in red despite the fine film of dirt covering it.

For over a month I sat with Sujith, Mike and Arun after my work at Kizhakkambalam. The days were exciting in many ways – besides meeting a fine set of brains over work that was quite novel for me and the scenic drive, I was at that time also dating an upcoming actress who lived nearby. My tallest claim to technology was the occasional updating of a WordPress blog platform, the one you are reading, which dropped me like a hot potato as soon as these guys began talking API, native and hybrids. Some of the demands I made were nothing short of exasperating and I could easily imagine the team hugging each other, moved to tears of joy, each time I left their office. I roped in another unsuspecting friend of over 20 years, Sumesh of Zigma Solutions, who handled the admin and maintenance of my websites, to tutor me on mobile tech and development jargon. It really helped – I now kept nodding my head sagely when the Infintor guys told me something wasn’t possible instead of shouting at them or threatening to take my business elsewhere.

The readying of the beta version was celebrated over lunch at a popular restaurant in Kakkanad which had, coincidentally, freedom as the décor theme. I assured the team that they weren’t free, but far from it, as I was taking my app for some ground survey into the heartland of agrarian Kerala – Wayanad and nearby regions in the north of the state.

And I would be back.

Research and Raman chettan

Around my birthday week in May that year, I took off for two weeks to be on the road. While one breakup was officially over – my lover of two years sent me a happy birthday note with an accompanying photograph of she and her much younger, new boyfriend – I was going through another with the actress. No better place to get a grip on life than on the open road, behind the wheel giving you a false sense of security and control. I checked into a swanky resort and a heritage homestay for a week each, treated myself to extended massages and copious amounts of alcohol. By dint of being in forest peripheries, a walk to the dining hall or the swimming pool qualified as grade two treks. I became friendly with all the staff, some of whom were effusive and warm north easterners delighted to see somebody as lonely as themselves, and I managed to score as well. I will say again, it doesn’t grow anywhere better than along the Western Ghats.

Talking to the locals, I was told about Cheruvayal Raman, a legend in the farming sphere, a fugleman when it came to preserving traditional methods. One sweltering noon, I drove to his village Valliyoorkavu tracing the banks of the Kabani River which flowed robustly. The short walk from my car to his house had me drenched in sweat and my shirt stuck to my back like cling film. Raman ushered me into a darkened room of his 150 year old house, thatched with palm leaves and made of adobe walls. Nowhere else before have I felt pleasanter, just wanting to curl up in a corner and go to sleep. Probably sensing what I wanted, his wife came with a rolled up bamboo mat and spread it on the floor. It transpired that in these tribal houses visitors sat on the floor and city slickers like me, who made a fool of themselves looking for chairs, were given the mats to sit on.

Taking me by surprise, soon as I explained to Raman chettan what my app was all about, he embarked on a panegyric and proclaimed it a desideratum of the times.

“Your app promotes the age-old barter system,” he said. “Anything that aids exchange will be virtuous (punyam was the Malayalam word he used) – it will help develop not just relationships but also build trust. Not to say benefit the farmer in the process.”

The feedback I gathered from others too was largely positive; the only obstacle being an intransigence to believe that the services – exchange, buying and selling of vegetables and fruits – were for free and that Farmfrnd itself wasn’t selling any of these directly. This opened my eyes to how deeply embedded was the profit model when it came to mobile apps. Not that it was such a far-fetched thought either – I had by now spent over three lakh rupees in developing the app and engaging additional consultants and revenue streams had to be thought of, eventually. But a few changes – additions to the list of available products – and ease of finding products for buyers by clearly defined radii, the app was good for a pilot go.

The lockdown and a launch

The rest of 2019, I was only fain to continue my Delhi-Kerala alternating schedules. End of the year, I decided to ride home for Christmas on my new motorcycle – a week-long odyssey I carefully chronicled across social media platforms with #DilliPalai; early 2020 I rode into the Rann of Kutch from Delhi, #RannRun. In short, the going was good till the pandemic brewing blew up on our faces and the consequent lockdown on March 24 which continues to this day in wavering severity. All the hard riding, in hindsight, seemed like I could grok what was coming. Anyway, I have been grounded, in my hometown Palai, for over seven months now – the longest since I left in 1996 for the post grad campus and soon after for work – and it’s the memories of the rides that keep me sane. That, and my work on the app and a book quietly released on Kindle which was more an exercise in responsibility and an attempt at equanimity and catharsis.

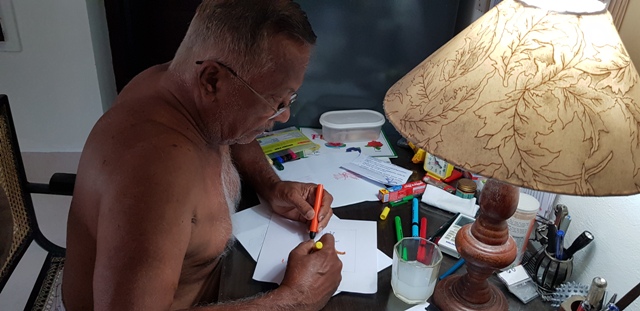

During April and May, I planted over 100 tapioca and 50 yams besides bananas and vegetables. It was not just my love for farming but also a media propelled scare of an impending famine which hastened my hoe. Taking a toll on my budgets as well as delaying the plans was that I had decided to make some more changes to the app. Fortunately for the tech team, they had their plates full even during the lockdown so they had to accommodate me by working overtime or late into the night. Meanwhile the aestivating summer made way for an inundating monsoon; Kerala, which was a lodestar when it came to resisting Covid in the beginning, succumbed with the highest TPR in the country. As I write, the number of per diem cases is the maximum. Things might change soon for the better, it is expected.

Around August this year Farmfrnd was re-submitted to Google Play which took a while going live due to apparent traffic. Seemed like it was not just me who was nursing application ideas and crunked about the lockdown according ample time to get around to them. The months that followed were used for trial runs among family and friends and sorting some niggles. Much to the consternation of the developers, I changed the design – again. I had managed to keep transactions within three clicks and I thought the interface had to support this ease; we toned down on the graphics. This was also done keeping in mind the target customer, the farmer, for whom the phone was an unavoidable encumbrance, a modern millstone – the lesser to do with it, the better.

The official launch of Farmfrnd by Mani C. Kappen was facilitated by Eby Jose, who handled the MLA’s media affairs, who was also my friend. Eby’s K.R. Narayanan Foundation – named after India’s 10th president who hailed from nearby Uzhavooor – did exemplary work in local development and thought it befitting to associate with the app. Due to Covid-mandated attendance restrictions, the event held at the auditorium of a prominent local hotel was not public. However, filling up the permitted numbers were a host of luminaries from local political and farming circles. While I shared my ‘tapioca in the trunk’ story to the audience, the MLA rightly observed ‘necessity is the mother…’

Talking about mothers, I stood with mine some days ago looking at the tapiocas I planted in April this year, which are man-high now, reminiscing how we went around town trying to find a buyer.

This time I hope to do that with three clicks.