“December is a safe time to be in Kashmir,” assured our host and partner, a valley resident. He was – still is – among the few Hindus who did not flee the valley following the vicious uprising against them during the 90s – when thousands of Hindus fled Kashmir to escape humiliation and mutilation followed mostly by death. More than feeling assured, the recklessness that comes with love made us believe what this bona fide Kashmiri said. The funding corporate had already mapped out our itinerary in the valley – we were to visit the least developed areas. In other words, the areas marred most by militancy, where taking up gun soon as you could hold one was an alternate job option for the youth overlooked by the development schemes of the mainland government. We were to do a recce of Anantnag, Budgam, Sopore and Kupwara to finalise venues to set up livelihood training centres.

Militancy in Kashmir thrives on two moral platforms – separatist and Islamist. It all began in 1947 when the then Hindu maharaja Hari Singh decided to hitch his mostly Muslim wagon to India. There was plenty of autonomy at first – India was to handle only defence, telecommunication and foreign affairs – a portfolio which widened considerably over the years. Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front which today morphed into the Hurriyat Conference, Hizbul Mujahideen – today less a threat because of its mostly dead leaders and members, and the most active, ISI-supported Lashkar-e-Taiba – have all been fighting for the heroically labelled struggle for ‘self determination’ in the valley. In the process the struggle has left at least a 100,000 dead, including the missing.

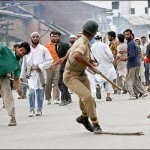

If Kashmir is indeed the ‘paradise on earth’ I know by now that angels tote guns. In many townships across Kashmir, uniforms outnumbered the pherans and the pyjamas; the state is among the heaviest militarised areas in the world. Our host lent us his car – a Maruti 800 that stood at a perpetual angle, thanks to fractured axle – for which I forgave him when he decided to opt out. We could do with the quiet. And the space. The roads were pretty decent if I was expecting shell craters. Anantnag has historically been a trade centre due to its central location – a hub of carpet and shawl making. We spent the evening roaming over the magnificent ruins of the Martand Sun Temple which, despite a focused approach to destruct it by Sultan Sikander during late 14th century – earning him the sobriquet of ‘Butshikan’ meaning ‘idol breaker’ – still looms large and majestic in places. The disconnected passages, despite the ravages of centuries ago, still retained some mystery of the eyes connecting from behind veils, the resounding echo of the fading nupur frolicking into the darker corners. The rust-golden rays of the setting sun danced over the corrugated slabs of the filigreed stones which held their crinkly heads high like the unbending patriarch of a fading pedigreed family. The descending nip of the winter night and the twilight’s sternness reminded us that we had to retire before curfew hour; we were put up at the houses of one of the programme partners. After 7pm, people were generally discouraged from venturing out by patrolling cops who gleefully interrogate you till your boxer size.Anantnag to Kupwara is less than 150 km and usually takes a little over two hours. But we had to stop along the way – to inspect and film – at the programme partners’ facilities at Budgam and Sopore. We started early next morning, a prayerful Friday, a day which has always evoked a mixture of emotions – some pious, some potent. The prayers offered at the local mosque were for a youngster who was reported missing by his family and presumed dead by everyone – tortured by the police. Soon after the afternoon namaz, a procession was held on the main street of Sopore. Slogans against India and the army’s highhandedness were hurled in right earnest, the military police stood without batting an eyelid, emotionless, tautly immobile behind a barricade of mean-business lathis. Those were the early days of the Intifada; the gradually swelling crowd stooped down to pick up stones and rocks and other discarded heavy objects from the main street.

Sopore still continues to be a flashpoint in the militant history of Kashmir. As recent as December 18 this year police killed five militants who belonged to Lashkar-e-Taiba. That afternoon we were passing through, fortifications – truckloads of grim men in military fatigues – were being deployed from Srinagar to Sopore. Earlier that day, around noon, we lunched at an elegantly latticed house of one of our programme partners from Srinagar; it was here we learnt about the incidents at Sopore. Soon as they heard the news, the family went about preparing our bedroom; confrontation with the army anywhere in the Valley meant downing shop shutters, schools kids instructed to hurry home as fast as possible and everybody on the streets racing the fast approaching dusk to turn in. After the generous portions of rogan josh and rice washed down with stream-cooled Coke for lunch I was raring to go; a fulfilling meal should always be followed with action.Once again the family tried to talk us out of travelling as we sipped the exotic kahwa – a topper for most Kashmiri meals. The green tea with a dash of extra spice was so invigorating and calming that I even patted my angular Maruti 800 before shuffling my lanky limbs into it. The town wore a deserted look; still you could detect the anxious eyes peering through the numerous holes in the living walls and the minarets. The saffron fields lolled on either side of the road. Sufi shrines with peeling domes exposing grey concrete and dust-covered weeds shrugging their way down lay scattered. The mosques cum madrasa appeared intermittently which were better kept and more green – fringed on all sides by flowering plants laboriously tended to by the resident students.

The Disturbed Areas Act – viewed as draconian by most in Kashmir, understandably – gives the army immense power that they can shoot to kill anybody out of suspicion, questions will be asked later. That is, if anybody asks. When a convoy is out on the road, civilians are not supposed to go anywhere near them. This, I was told later, was for our own safety as the convoys although an imposing show of formidable strength, are sitting ducks for militant attacks. When we were passing through, they were en route to an agitating Sopore, making it longer than usual. I overtook the first truck – which must have been at least 80kmph – I remember pushing my pre historic Maruti 800 till it overtook with a violent shudder, bravely holding itself against the force of the field winds, the rumbling camouflaged giant truck with canvas flapping on all sides like ears in disarray. Then there was another and another and another, we gaily counted 27, as we zigzagged in and out of the convoy where each truck seemed to be chasing the one in the front. The gallivanting continued until a heavily armed army man wearing a bulletproof vest standing by the side of the road jumped right in front of our car and levelled his Kalashnikov at us with a quiet menace.

Swerving sharply I lost control of the car which ploughed into the adjoining field, kicked up moist dust which clouded us for a few long moments. I heard several disjointed grunts and feared the axle would have anchored itself into the ground making us immobile. Soon as the dust settled, I gathered my bearings and floored the car straight for the road that somehow seemed to me a long way off. Minu sat frozen staring at the army man through the window who was trotting unhurriedly towards us. Shifting gears, I gunned for the faraway road – which was the only way out. I expected resonating tick-tick metallic sounds which thankfully never came. Back on the road, I peered fearfully through the rear view mirror and saw the adamant muzzle still hell bent on us. A little side road a few kilometres away and I pulled into it. We both got off the car and hid behind a tree, hands ready to go up and mouth pursed and ready to holler some peaceful words. Only that no sound was coming out. Then again, bullets would be faster than uttered incoherence.The trucks all sped past towards their urgent business in Sopore. Though we had only barely left the capital outskirts, we did not dare to head back fear of the Kalashnikov still out there. There would also be embarrassing ‘didn’t-we-tell-you-so’ questions and hidden sniggers. Though we definitely deserved it for being indefinitely stupid, we decided to spare us any further trauma and headed for Sopore. I sat sucking in the sights that breezed past in the soft afternoon sun with a new life. In the distance were rows and rows of mountains with powdered snow rustling all around it, but leaving the very top like an erect nipple. The serene meadows on both sides of the road had livestock grazing peacefully, looking up occasionally at the sun as if to check how far more to touchdown. Meandering streams gushed merrily beating themselves into frothy curtains against the glistening rocks lining the bank. An occasional cowherd stood in his flapping overalls like Moses, replete with the staff, blowing out miniature tobacco clouds from specially rolled beedis. I stopped the car and got out.

Salman Rushdie wrote about the ‘lush valleys, the streams and the meadows’ of Kashmir. And it was all here, condensed into one frame, probably rewarding us for the dilemma we went through. My heart continued its relentless pounding. But this time the reasons were different.(While most of the photographs are from my successive trips to Kashmir, some have been sourced from Google as per the requirement. If anybody has any issues, please do let me know and I shall knock it off…)