For a full ignoble minute I remember thinking Conan – Barbarian and Destroyer – was right. These halitosis hurricanes ought to be thwacked.

I lay sprawled clutching handfuls of ebbing sand, my heart trying hard to squeeze itself out through the ribcage. Shooting stars swam in slomo in front of my eyes and I would have breathed through my ears if I could. After a while when I sat up I was told of many others who didn’t – sit up, that is. They couldn’t as their hearts had quit. My desert guide cum camel minder also beamed that if I hadn’t ducked the kick could have pulped my eyeballs or shattered my nose or unhinged a few teeth. Usually all of these. I don’t remember any split-second reflex but vividly do wincing with pain and my chest welling up welter-red.

Like most creatures of merit the camel too gives in to bouts of impatience and intemperance – frequent during mating season – or sometimes just bad grace. Nobody can really say what irks it or predict when. But if you come out alive they all say you are lucky and will help you review the circumstances. A few winters ago I was bivouacking along the border dunes of Jaisalmer. One particularly sunny day I decided to cut across under the belly of my bull camel – like I’d seen my guide do many times. I was too drained to draw a tedious perimeter around the lolling dromedary. Thump! A powerful back hoof cannoned me a few metres away from its heaving belly.

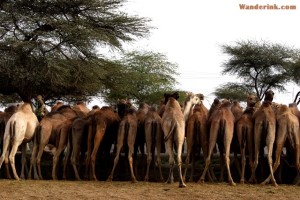

“They feel threatened when somebody strange gets too close to their organs.” The minder explained what caught his ward’s goat later that night. “Just like us.” He chuckled. Sorties from both sides of the undulating, blurred border thundered through the metallic sky pricked silver by unblinking stars. We sat swathed in wafts of greyish blue pungency. My bête noir was an oasis of calm, chewing his food steadily, peacefully like a seminarian at dinner. A rest well-earned: All day he careened over sand embankments carting heavy camping equipment, food and water through foot-deep sand, quashing desert scorpions scurrying for cover without missing its gangly gait, ambled on under the sweltering midday sun which kept even the shadows in the shade, sneering at the cacti. Of course, he had also vented a vehement disapproval for trespassers into its billowy nethers.

Though I didn’t exactly come out unscathed – my backpack had to be dragged the rest of the trip – the incident didn’t dampen my fondness – a sort of fetish, I suspect – for riding. Camels and horses, elephants, buffaloes, donkeys and yaks – I have broken many tight itineraries and tighter budgets, nearly broken my limbs even to ride them while on assignment. This yak in Tibet not only shook me to the ground but wanted to stomp me till my screams brought the situation to the owner Sherpa’s notice who I must say just continued his wracking laughter. Last month while passing through Bikaner in Rajasthan somebody mentioned the ‘camel centre’ for its wonderful research work and technological innovations.

“Do they have camels for riding?” Was my only query.

The National Research Centre on Camel (‘camel centre’ locally) is about 10 kilometres from Bikaner city and is open from 2pm to 5:30pm. The hours are perfect for those who come to the city for its more famous attraction – the Junagarh Fort, easily the best fort in the country for its multiple mahals and rich museum galleries and not the least for its photography-friendly policy. After an enriching half day at Junagarh, you can lunch and relax at the decent cafeterias on the fort ground. Hire an auto rickshaw from outside the fort to the camel centre – a dusty ride through blistering, deserted stretches worsened further by countless speed-breakers and numerous municipality sweepers with zigzagging brooms coaxing sand from the road to either side.

Tip: There are auto rickshaws waiting outside the Junagarh which will take you to the camel centre. A one-way trip can be wrested for Rs 100. But it’s better to ask them to wait at the centre – it’s very difficult to find a transport back – for which you need to pay Rs 200.

Many balked at the camel milk parlour while some shuddered, unwilling to even take a second glance in the general direction. I had a bottle each of pistachio and chocolate flavoured milk and one kulfi to go. I did good as I was to learn later from the museum that camel milk is three times richer in vitamin C and has 10 times more iron than cow milk. In addition to the high vitamin and mineral content the milk has anti-bacterial, anti-viral and anti-tumour properties which makes it effective against HIV, hepatitis C, Alzheimer’s and cancer. There is no substantial taste difference even – slightly chalky, if you try it non-flavoured – which makes one wonder why it is not available at the corner store.

The centre has made commendable biological breakthroughs with regard to the camel’s adaptability to the changing climate, its ability to survive in different environments, processing and commercialisation of different camel products especially milk. Though the centre has nothing to do with camel meat, it is sought-after in many countries as it is healthier than beef due to lower fat and higher protein content. The museum also documents the strides made by the centre in developing the camel’s draught power. It was draught animal power (DAP) which first supplemented human energy more so in the agricultural sphere. DAP has been historically used in milling flour, farming, cartage of timber and road and railway construction. Camels played a phenomenal role in the laying of railway tracks in the arid Australian outback. While diesel-powered vehicles changed our agrarian landscape, rising fuel prices and global warming has necessitated we re-visit DAP. The camel centre is spearheading our efforts in the direction.

Despite such commendable work what’s showcased as result – and the way they are exhibited – is lacklustre. Being a centre of active research I expected some sort interface with the people behind the innovations. Forget the scientists, even the Raikas, the traditional livestock specialists of Rajasthan, who are employed as helpers didn’t seem particularly conversant about the centre. Instead of probably taking groups of tourists on guided tours to some of the accessible labs, such areas are indifferently marked as beyond bounds. An earnest effort has been made at the museum to explain landmark inventions and milestones but with mostly photographs and lengthy descriptions they miss the mark and we lose interest. What really catches typical tourist fancy are the camel teeth necklaces, bone artifacts and leather bags arrayed in curio shops. ‘Made from milk teeth and dead bones,’ we are assured.

Rajjo seemed to be in a hurry; she unfolded skywards just as I was manoeuvring myself around her hump. We passed by a rapt line by the feeding tank, downcast ones in the quarantine, frisky ones milling around a water trough and a birthing one. We were back to where we started in less than 10 minutes. I got myself a coupon for one more run and handed it to the red-turbaned Raika.

“But it’s the same route.” He told me in his Simon Pure-simplicity.

“It’s not about the route.” I assured him.

The kind of gem that defines quality travel writing. Thanks for sharing this experience. And the birthing video? What an opportune capture!

Still, am left wondering about the teeth, bone and hide accessories you mention in passing…

It’s such a kick…coming from you 🙂 Thank you. Right you are about the accessories… when I am riding one, I wonder ‘hey will I bag this one?’