At Kachowri Gali Chowk the bereaved family halted abruptly and looked around flummoxed: where did their dear departed go?

Narrow lanes threaded by paan and tuck shops met their gaze. Cows pootled along like shuffling gum-chewing teenagers. Widows clad in white cotton saris with faded neelam-blue borders sat dignified at the doorsteps of dharamshalas, hands clasped in prayer – audible only when they took a break to ask for alms. There were reiki and yoga centres claiming reviews on TripAdvisor and confectioners claiming references in Lonely Planet. Flower sellers sat aligning their wares with the changing shade.

The lane itself was carpeted with red gobs splattered like fallen stars. Tourists stood outside the capacity-packed Blue Lassi Shop (‘Near Burning Ghat’) impatiently awaiting their turn, fidgeting in the heat, humidity and humdrum. They were jostled and shoved by the professional pallbearers who ferried dead bodies in embellished stretchers to the burning ghats* – their chants changing inflection in accordance with pedestrian traffic; the brisk – and brusque – cogs in the wheel of an economy that throve on death.

By the ghats

Farther down from the chowk, closer to the Ganges, priests sat under bamboo-matted umbrellas waiting to be hired for pujas related to cremations and ancestral remembrances. Each of these umbrellas has a fixed location just like brick and mortar shutter shops. And just like shutter shops, these umbrellas are also handed down from one generation to the next – a family business. Call it value-add or keeping up, they also act as cloak rooms – clothes and valuables are entrusted here for safekeeping when clients go for the holy dip. Shops selling religious knick-knacks, beedi stacks and pouched tobacco have taken up most of the leafy corners.

Widows and destitute women sat in clamorous rows benedictions handy for the benevolent: ‘May you have hundreds of children.’ Equally at hand were condemnations for the niggardly: ‘Your photos are not going to feed us.’ I was the happy – and the hapless – recipient of both effusions. Long-haired mendicants of sturdy deportments sat gazing out over the Ganges certainly seeing a lot more than a regular pair of eyes. Some old men clad in towels flexed their oiled limbs in the sun as they watched amusedly boats disgorging tourists and photographers by the dozen.

“Have you ever seen the ghats from a boat on the Ganges?” I asked one whose wide smile I mistook to be exceptionally friendly.

“Why should I?” He asked a tad irascible and replied, “I live here.” And went back to piston-working his legs – the smile intact; maybe that was how he held up his eye glasses.

By boat

As long as you don’t live here the best way to take in the ghats is from the Ganges. My boat ride that morning was arranged by the Uttar Pradesh Tourism Department as part of their well-meaning efforts to promote the recently branded Heritage Arc circuit. I chose Varanasi** for the ghats and Sarnath nearby. I’d choose Varanasi again if given a choice but there’d be Baba Thandai too in addition to the two mentioned. (Ok, there’d be more – like the little known and spoken about Assi Ghat Kavi Sammelan, the ‘spirit walks’ and a chance to listen to ‘Banaras baj.’) But that is a story for later. The boat ride started soon as the milky pre-dawn light transformed into the hazy rust of a smoky morning.

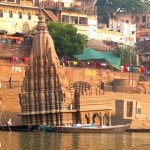

The ghats fringe most of the waterfront and are dotted with temples. Among the ‘nearly 100’ ghats that line the riverside the most popular ones are the Assi Ghat, Dashashwamedh Ghat, Manikarnika, Man Mandir, Rajendra Prasad, Bhosale and Scindia Ghats. There are a handful of small but important ones like the Manasarovar Ghat, Narada, Chausathi and Lalita Ghat which is built in the typical Nepali style and houses Pashupatinath – Shiva’s manifestation in the Kathmandu Valley. The Manikarnika Ghat is north of Lalita Ghat and is one of the busiest cremation grounds of Varanasi. It is hence noisy and noisome – you can smell burning flesh from afar – right from sunrise.

In the distance you can watch the Malaviya Bridge, which apparently marks the perimeter of the ‘holy area’ of Varanasi, slowly emerge from the smoke shroud as you close in towards the end of the boat ride. Dhobis can also be seen at work rhythmically thrashing copious curtains or other jumbo-sized articles – three continuous beats on the stone followed by a fourth dip in the water. ‘Boom Shankar’ was written in many places in clever fonts that resembled stereo speakers. Towards the end of the ride I came across a leaning temple submerged in the water which was introduced simply as ‘the leaning temple’ which I marvelled as a definite lure for the Japanese tourist flocking to Sarnath. Parlous probably but definitely most charming.

By lane

After disembarking from the boat and recouping from the sensory jolts that was life and death – which was responsible for the life – in the ghats, a guided walkabout took me through the Dashashwamedh, Rajendra Prasad and Man Mandir Ghats – this time through the back lanes. This was the living backend: firewood shops, napping and smoking pallbearers for hire, wholesale shops and lodges with ‘Ganges view.’

“Where does the firewood come from?” I asked Kunal Rakshit a tourist guide associated with ‘Experience Varanasi‘ which conducts walking tours through the city.

“We have social forestry in Chunar and Mirzapur,” he said. An electrical crematorium in the precinct not finding fervour was bad news; social forestry was the only way to tackle an unyielding mindset.

A higgledy-piggledy maze of bylanes; linger a bit for photographs and I had visions of sitting next to the old geezers and working out my legs with a permanent, misleading smile plastered across my face. While most cows stood right in the middle of the gali leaving just enough room for you to squeeze through – if you held your camera upraised with your hands – I saw one magnificently intelligent bovine bella sitting inside an open doorstep with a look that said she knew fully well what she was doing – making way.

After an interminable wait by when I had sweated out my body water to 30 per cent, came my turn at the Blue Lassi Shop (‘Near Burning Ghat’): worth every shoulder and shout I was meted out by the pallbearers in tearing hurry. The thickest of yoghurt served in matka cups with its rejuvenating wet-earth fragrance, garnished with broken pistachios and almonds and that extra love – additional makhan, homemade butter, on the top. It helped the lunch later was fancy vegetarian – else I would have bawled my heart out when I sat pecking from a fellow traveller’s plate.

Propelled by lactic burps I emerged from the Blue Lassi Shop (‘Near…) and had to count one cathartic foot after another through the historic Dal Mandi – a once upon a time red light area. This today is primarily a wholesale market for garments, household items and garishly coloured plastic flowers. Any query pertaining to its not-very-old reputation is shot down vehemently. I glanced up a row of multi coloured chudiyan that hung glittering in a shop and saw a window with peeling stucco work held up with fresh coats of paint. Imagining a gorgeous tawaif sitting on its ledges probably humming a mujra number teasing a swain below wasn’t such a stretch. We exited Dal Mandi at the Langda Hafiz Masjid.

Banaras is a city that seems to have succumbed to a condition of permanent contraflow; the hardly 10 km to Sarnath takes the better part of an hour. But the good thing is that everything the city is famed for is within walking reach – the ghats and the temples, the kushti akharas, paan wallahs, bhang and thandai shops. There is the monumental Gyanvyapi mosque, a disputed site, sharing boundary with the pilgrimage hotspot, Kashi Vishwanath Temple. The frayed yellow St Thomas Church believed to be over 300 years old at the Girija Ghar crossing across the street from the popular PDR Mall is a city landmark. Both these are not part of regular itineraries. Neither is the Aghori Ashram tucked not very far away with all the adjunct rumours and baseless ballyhoo.

A walk through the bylanes of Pilikothi will bring you up and close with the famed weavers of the city – an increasing number of whom are giving up the traditional handloom for powerlooms, in the process landing the famous Banarasi sari in a survival crisis.

You also get to meet men like Ansari bent intent over the warp passing through the reed of a handloom as ancient as him.

“You are as energetic as a 16-year old,” Kunal greeted him. “How old are you really?”

“I’m 17,” Ansari replied, his mischievous eyes twinkling through the fading light of the dusk.

*Ghats is a generic term used to describe the stone steps that lead down from the 18th and 19th century pavilions and palaces to the banks of the River Ganges, where bodies are cremated and related rituals carried out presided over by Hindu priests. There are a total of 82 ghats – a fluctuating number as businessmen with clout and politicians keep adding to it. The ghat here is different from the ghat in ‘ghat roads’ where it means mountain.

**Varanasi and Banaras (Benaras) are used interchangeably as they can be used interchangeably.

6 Comments

Chaitali Patel

Fabulous account of your trip! Long account and I read all of it, so that will tell you how much I enjoyed it! 🙂 I have been Benaras as a child and have memories of my visit, but think its time to explore it again.

Admin

Chaitali, am really glad the length didn’t come in the way of your enjoyment and your reminiscences. Banaras is a heaving, breathing organism and puts a different face for different people, or maybe even for same people at different times. I mean, yeah its time. Thanks for stopping by.

Manjulika Pramod

This is the real Banaras… Varanasi!

I loved reading the account. This was absolutely lively.

Admin

Thank you! Manjulika!!

Kunal Rakshit

Beautifully put in words!! It was a delight reading your interpretation of Varanasi. We at Experience Varanasi are committed to give an authentic and off beat insight of the city to our Guests.

Thanks for the mention Thommen.

Admin

I do not interpret anything, Kunal…I believe in sticking to saying what I see, felt. I leave it to you to interpret 🙂 Thanks, anyway!