Seldom do we have a say in the situations we find ourselves in. But where we do is whether we come out of them. And how: Shaking like a dry leaf in a harmattan but unscathed, barely scraping through and lucky to be alive. Or what we make of them: Wiser, more patient, better streetsmarts, a newfound appreciation for life. Even as wellsprings of opinion on everything under the sun or a screaming expert on national television. Every recount accords a reinvention: Apoplectic juddering and sweaty brows of a private reminiscence can take on a dismissive conviviality during public narratives without diminishing the event. After all it is the profound incident that makes everyman a showman.

It is both a profligacy of the media-ridden world and the proliferation that issues from it that we have come to take acts of heroism and feats of daring in our stride. The drama, we realise, is missing from the Drama in Real Life of old Reader’s Digests. This watering down is a handiwork, a requirement, a proverbial expectation even, of Time. So when my dad told me about his kidnapping in Lagos many years ago when it was still the Nigerian capital my first reaction was ‘boy, it must’ve been some adventure’. The sizeable sum he lost, a chunk from our final remittance was ‘some real rotten luck’. But when he told me about the passport he got back because he demanded it be returned from his gun-wielding assailants I saw that shiny, gritty constituent that makes an evergreen adventure: balls. And an amazing presence of mind that saved his glasses as they readied to lob him from the moving car.

No one else seems to worry, as I do, that the money demanded by someone whose finger hovers over the trigger of an AK-47 is less a tip than a ransom. (From ‘Every day is for the thief’ set in Lagos, Nigeria by Teju Cole.)

It was the final year of our stay in Nigeria; the Christian-Muslim tensions that were to eventually erupt into widespread clashes leading to death in thousands had begun to simmer. We were in the extreme northwest state of Sokoto and were spared of the frequent tribe-specific chest-thumping and tyre-burning of northern Kaduna and Kano, flashpoints where many friends and colleagues of my folks from back home in Kerala were quartered.

In a rare instance of forward-thinking, education was deemed integral to development in the nationalistic years post late independence in 1960 and teachers from India were enticed with high remuneration packages and attractive remittance policies. Hundreds, on leaves of varying durations from the educational institutions of Kerala, descended on Sokoto state which itself was carved out seven years later and every prepossessing Sultan and pretending Ozo (a local title of respect which is invariably bought) started a school.

Since the bigger, faster aircrafts were rare then my dad took a regular Cessna one morning from Sokoto and landed in Lagos almost four hours later. He remembers a loquacious tyro in command who made it a point to introduce himself personally to everyone who boarded – as if according a note of thanks for trusting him with their lives. After extended vacillations through ominous nimbostrati they landed in the humid aridity of Lagos in the southwest tip. Old remittance hands had cautioned him against using the popular public carrier, the danfo – a 14-seater decrepit mini bus of peeling yellow. My dad, an avid watcher of people and life even today – the prettier the better – decided to save the danfo for later, maybe for getting into Onikan, the heart of old Lagos. He was also planning to visit the National Museum there in the afternoon after his bank work where a friend would meet him. Till the bank on Victoria Island it would be a cab then. The bulk of Naira bundles were in his overnight case while one – dedicated to douceur; Nigeria was and continues to be openly corrupt – was in his trouser pocket, discreetly outlining temptation, probably.

A cab pulled up as soon as he exited the airport and the driver declaimed dad to climb in without even asking where he was headed to.

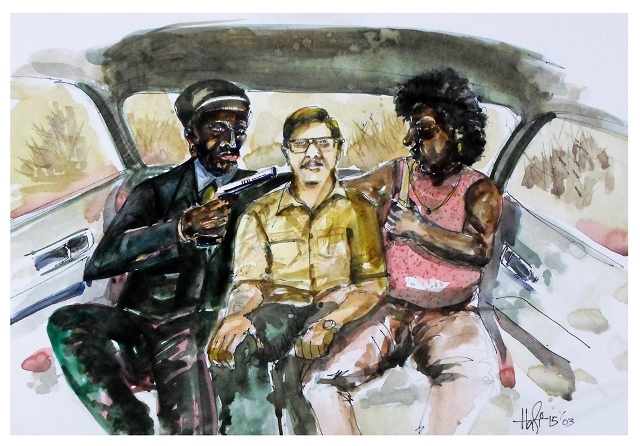

“Victoria Island,” said dad as they sped away from the bustle of the airport. The cabbie screeched to a halt as if he changed his mind about the fare. Before dad could ask what was going on a stocky and an incongruously dressed pair got into the backseat – one in a fancy tux with a tribal headgear and the other in a more suitable singlet. They got in from either side of the car, squeezing dad immovable with their bulky musculature.

“I was actually thinking about changing my mind on taking the danfo – if a cab was so bad, imagine a public carrier – when the guy in the suit took out a gun and pointed at me.” Dad recounts with amused eyes and an even-keeled voice – from probably reliving the incident a thousand times in his mind since that day. It still hadn’t occurred to him that it was a robbery. So he turned to look at the singlet guy as if the tux’s unfinished business was with him. The singlet had to pull out a switchblade for dad to realise that he was the business.

‘Ahmadu Bello Way’ dad remembers seeing a roadside signage while travelling thus transfixed. The name was familiar as it was the address of some embassy he had to go to the next day. The over and under dressed duo had relieved him of his overnight case – flung it over to the front seat – and also pulled out the wad of cash from his pocket. Many oneiric minutes passed before he realised that they were looking for a secluded spot to defenestrate him. That was when he asked for his passport back; he remains clueless at what made them return his document. He, possibly rightly, subscribes it to the whole lot of money that had just come their way. All in less-than-a-day’s work.

“Were you ever worried that they might have killed you?” I asked.

“If they wanted to they would have by now, right?”

Now, that was some cool-headed thinking. Yes, this guy had every right to ask for his passport back.

“Not just that, they even gave me money to catch a danfo to the National Museum.” His nonchalance only compounded my incredulity.

As they slowed the car down the singlet moved across the seat over to where the tux was and dad immediately got wind of what was about to happen. He removed his glasses and cupped it tightly in his hands and tucked his head hard against the chest.

“Even before they pushed me out I had curled up into the safe rolling position of the foetus,” he said.

“How did you know going foetal was the safest?”

“I taught zoology, remember?”

The twinkle in his eyes belied the straight face.

My sincere gratitude to ex-colleague, great friend and immensely gifted artist Harikumar for the superlative rendition of an episode – almost as if he was there.